Building Serverless Frontend Applications Using Google Cloud Platform

Recently, the development paradigm of applications has begun to shift from manually having to deploy, scale and update the resources used within an application to relying on third-party cloud service providers to do most of the management of these resources.

As a developer or an organization that wants to build a market-fit application within the quickest time possible, your main focus might be on delivering your core application service to your users while you spend a smaller amount of time on configuring, deploying and stress testing your application. If this is your use case, handling the business logic of your application in a serverless manner might your best option. But how?

This article is beneficial to front-end engineers who want to build certain functionalities within their application or back-end engineers who want to extract and handle a certain functionality from an existing back-end service using a serverless application deployed to the Google Cloud Platform.

Note: To benefit from what will be covered here, you need to have experience working with React. No prior experience in serverless applications is required.

Before we begin, let’s understand what serverless applications really are and how the serverless architecture can be used when building an application within the context of a frontend engineer.

Serverless Applications

Serverless applications are applications broken down into tiny reusable event-driven functions, hosted and managed by third-party cloud service providers within the public cloud on behalf of the application author. These are triggered by certain events and are executed on demand. Although the “less” suffix attached to the serverless word indicates the absence of a server, this is not 100% the case. These applications still run on servers and other hardware resources, but in this case, those resources are not provisioned by the developer but rather by a third-party cloud service provider. So they are server-less to the application author but still run on servers and are accessible over the public internet.

An example use case of a serverless application would be sending emails to potential users who visit your landing page and subscribe to receiving product launch emails. At this stage, you probably don’t have a back-end service running and would not want to sacrifice the time and resources needed to create, deploy and manage one, all because you need to send emails. Here, you can write a single file that uses an email client and deploy to any cloud provider that supports serverless application and let them manage this application on your behalf while you connect this serverless application to your landing page.

While there are a ton of reasons why you might consider leveraging serverless applications or Functions As A Service (FAAS) as they are called, for your frontend application, here are some very notable reasons that you should consider:

- Application auto scaling

Serverless applications are horizontally scaled and this "scaling out” is automatically done by the Cloud provider based on the amount of invocations, so the developer doesn't have to manually add or remove resources when the application is under heavy load. - Cost Effectiveness

Being event-driven, serverless applications run only when needed and this reflects on the charges as they are billed based on the number of time invoked. - Flexibility

Serverless applications are built to be highly reusable and this means they are not bound to a single project or application. A particular functionality can be extracted into a serverless application, deployed and used across multiple projects or applications. Serverless applications can also be written in the preferred language of the application author, although some cloud providers only support a smaller amount of languages.

When making use of serverless applications, every developer has a vast array of cloud providers within the public cloud to make use of. Within the context of this article we will focus on serverless applications on the Google Cloud Platform — how they are created, managed, deployed and how they also integrate with other products on the Google Cloud. To do this, we will add new functionalities to this existing React application while working through the process of:

- Organizing application workflows using the Google Cloud.

- Storing and retrieving users’ data on the cloud.

- Creating and managing cron jobs on the Google Cloud.

- Deploying Cloud Functions to the Google Cloud.

Note: Serverless applications are not bound to React only, as long as your preferred front-end framework or library can make an HTTP request, it can use a serverless application.

Google Cloud Functions

The Google Cloud allows developers to create serverless applications using the Cloud Functions and runs them using the Functions Framework. As they are called, Cloud functions are reusable event-driven functions deployed to the Google Cloud to listen for specific trigger out of the six available event triggers and then perform the operation it was written to execute.

Cloud functions which are short-lived, (with a default execution timeout of 60 seconds and a maximum of 9 minutes) can be written using JavaScript, Python, Golang and Java and executed using their runtime. In JavaScript, they can be executed using only using some available versions of the Node runtime and are written in the form of CommonJS modules using plain JavaScript as they are exported as the primary function to be run on the Google Cloud.

An example of a cloud function is the one below which is an empty boilerplate for the function to handle a user’s data.

// index.js

exports.firestoreFunction = function (req, res) {

return res.status(200).send({ data: `Hello ${req.query.name}` });

}Above we have a module which exports a function. When executed, it receives the request and response arguments similar to a HTTP route.

Note: A cloud function matches every HTTP protocol when a request is made. This is worth noting when expecting data in the request argument as the data attached when making a request to execute a cloud function would be present in the request body for POST requests while in the query body for GET requests.

Cloud functions can be executed locally during development by installing the @google-cloud/functions-framework package within the same folder where the written function is placed or doing a global installation to use it for multiple functions by running npm i -g @google-cloud/functions-framework from your command line. Once installed, it should be added to the package.json script with the name of exported module similar to the one below:

"scripts": {

"start": "functions-framework --target=firestoreFunction --port=8000",

}Above we have a single command within our scripts in the package.json file which runs the functions-framework and also specifies the firestoreFunction as the target function to be run locally on port 8000.

We can test this function’s endpoint by making a GET request to port 8000 on localhost using curl. Pasting the command below in a terminal will do that and return a response.

curl http://localhost:8000?name="Smashing Magazine Author"The request above when executed makes a request with a GET HTTP method and responds with with a 200 status code and an object data containing the name added in the query.

Deploying A Cloud Function

Out of the available deployment methods,, one quick way to deploy a cloud function from a local machine is to use the cloud Sdk after installing it. Running the command below from the terminal after authenticating the gcloud sdk with your project on the Google Cloud, would deploy a locally created function to the Cloud Function service.

gcloud functions deploy "demo-function" --runtime nodejs10 --trigger-http --entry-point=demo --timeout=60 --set-env-vars=[name="Developer"] --allow-unauthenticatedUsing the explained flags below, the command above deploys an HTTP triggered function to the google cloud with the name “demo-function”.

- NAME

This is the name given to a cloud function when deploying it and is required. region

This is the region where the cloud function is to be deployed to. By default, it is deployed tous-central1.trigger-http

This selects HTTP as the function’s trigger type.allow-unauthenticated

This allows the function to be invoked outside the Google Cloud through the Internet using its generated endpoint without checking if the caller is authenticated.source

Local path from the terminal to the file which contains the function to be deployed.entry-point

This the specific exported module to be deployed from the file where the functions were written.runtime

This is the language runtime to be used for the function among this list of accepted runtime.timeout

This is the maximum time a function can run before timing out. It is 60 seconds by default and can be set to a maximum of 9 minutes.

Note: Making a function allow unauthenticated requests means that anybody with your function’s endpoint can also make requests without you granting it. To mitigate this, we can make sure the endpoint stays private by using it through environment variables, or by requesting authorization headers on each request.

Now that our demo-function has been deployed and we have the endpoint, we can test this function as if it was being used in a real-world application using a global installation of autocannon. Running autocannon -d=5 -c=300 CLOUD_FUNCTION_URL from the opened terminal would generate 300 concurrent requests to the cloud function within a 5 seconds duration. This more than enough to start the cloud function and also generate some metrics that we can explore on the function’s dashboard.

Note: A function’s endpoint would be printed out in the terminal after deployment. If not the case, run gcloud function describe FUNCTION_NAME from the terminal to get the details about the deployed function including the endpoint.

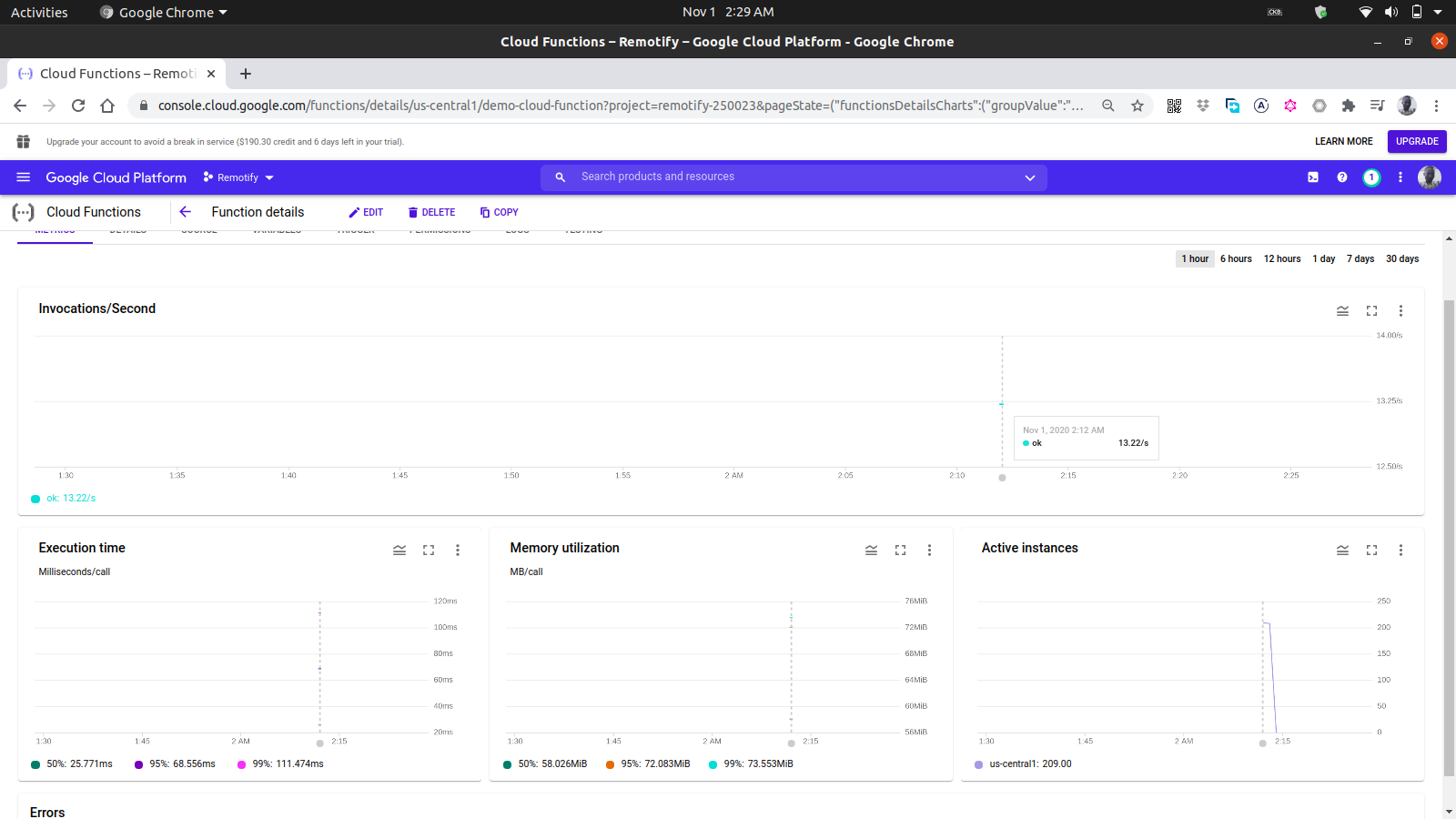

Using the metrics tab on the dashboard, we can see a visual representation from the last request consisting of how many invocations were made, how long they lasted, the memory footprint of the function and how many instances were spun to handle the requests made.

A closer look at the Active Instances chart within the image above shows the horizontal scaling capacity of the Cloud Functions, as we can see that 209 instances were spun up within a few seconds to handle the requests made using autocannon.

Cloud Function Logs

Every function deployed to the Google cloud has a log and each time this function is executed, a new entry into that log is made. From the Log tab on the function’s dashboard, we can see a list of all the logs entries from a cloud function.

Below are the log entries from our deployed demo-function created as a result of the requests we made using autocannon.

Each of the log entry above shows exactly when a function was executed, how long the execution took and what status code it ended with. If there are any errors resulting from a function, details of the error including the line it occurred would be shown in the logs here.

The Logs Explorer on the Google Cloud can be used to see more comprehensive details about the logs from a cloud function.

Cloud Functions With Front-end Applications

Cloud functions are very useful and powerful to frontend engineers. A frontend engineer without the knowledge of managing back-end applications can extract a functionality into a cloud function, deploy to the Google Cloud and use in a frontend application by making HTTP requests to the cloud function through it’s endpoint.

To show how cloud functions can be used in a frontend application, we would add more features to this React application. The application already has a basic routing between the authentication and home pages setup. We will expand it to use the React Context API to manage our application state as the use of the created cloud functions would be done within the application reducers.

To get started, we create our application’s context using the createContext API and also create a reducer for handling the actions within our application.

// state/index.js

import { createContext } from "react";

export const UserReducer = (action, state) => {

switch (action.type) {

case "CREATE-USER":

break;

case "UPLOAD-USER-IMAGE":

break;

case "FETCH-DATA" :

break

case "LOGOUT" :

break;

default:

console.log(`${action.type} is not recognized`)

}

};

export const userState = {

user: null,

isLoggedIn : false

};

export const UserContext = createContext(userState);

Above, we started with creating a UserReducer function which contains a switch statement, allowing it perform an operation based on the type of action dispatched into it. The switch statement has has four cases and these are the actions we will be handling. For now they don’t do anything yet but when we begin integrating with our cloud functions, we would incrementally implement the actions to be performed in them.

We also created and exported our application’s context using the React createContext API and gave it a default value of the userState object which contains a user value currently which would be updated from null to the user’s data after authentication and also an isLoggedIn boolean value to know if the user is logged in or not.

Now we can proceed to consume our context, but before we do that, we need to wrap our entire application tree with the Provider attached to the UserContext for the children components to be able to subscribe to the value change of our context.

// index.js

import React from "react";

import ReactDOM from "react-dom";

import "./index.css";

import App from "./app";

import { UserContext, userState } from "./state/";

ReactDOM.render(

<React.StrictMode>

<UserContext.Provider value={userState}>

<App />

</UserContext.Provider>

</React.StrictMode>,

document.getElementById("root")

);

serviceWorker.unregister();

We wrap our enter application with the UserContext provider at the root component and passed our previously created userState default value in the value prop.

Now that we have our application state fully setup, we can move into our creating the user’s data model using the Google Cloud Firestore through a cloud function.

Handling Application Data

A user's data within this application consists of a unique id, an email, a password and the URL to an image. Using a cloud function this data will be stored on the cloud using the Cloud Firestore Service which is offered on the Google Cloud Platform.

The Google Cloud Firestore, a flexible NoSQL database was carved out from the Firebase Realtime Database with new enhanced features that allows for richer and faster queries alongside offline data support. Data within the Firestore service are organized into collections.

The Firestore can be visually accessed through the Google Cloud Console. To launch it, open the left navigation pane and scroll down to the Database section and click on Firestore. That would show the list of collections for users with existing data or prompt the user to create a new collection when there is no existing collection. We would create a users collection to be used by our application.

Similar to other services on the Google Cloud Platform, Cloud Firestore also has a JavaScript client library built to be used in a node environment (an error would be thrown if used in the browser). To improvise, we use the Cloud Firestore in a cloud function using the @google-cloud/firestore package.

Using The Cloud Firestore With A Cloud Function

To get started, we would rename the first function we created from demo-cloud-function to firestoreFunction and then expand it to connect with our users collection on the Firestore and also save and login users.

require("dotenv").config();

const { Firestore } = require("@google-cloud/firestore");

const { SecretManagerServiceClient } = require("@google-cloud/secret-manager");

const client = new SecretManagerServiceClient();

exports.firestoreFunction = function (req, res) {

return {

const { email, password, type } = req.body;

const firestore = new Firestore();

const document = firestore.collection("users");

console.log(document) // prints details of the collection to the function logs

if (!type) {

res.status(422).send("An action type was not specified");

}

switch (type) {

case "CREATE-USER":

break

case "LOGIN-USER":

break;

default:

res.status(422).send(${type} is not a valid function action)

}

};

To handle more operations involving the fire-store, we have added a switch statement with two cases to handle the authentication needs of our application. Our switch statement evaluates a type expression which we add to the request body when making a request to this function from our application and whenever this type data is not present in our request body, the request is identified as a Bad Request and a 400 status code alongside a message to indicate the missing type is sent as a response.

We establish a connection with the Firestore using the Application Default Credentials(ADC) library within the Cloud Firestore client library. On the next line, we call the collection method in another variable and pass in the name of our collection. We will be using this to further perform other operations on the collection of the contained documents.

Note: Client libraries for services on the Google Cloud connect to their respective service using a created service account key passed in when initializing the constructor. When the service account key is not present, it defaults to using the Application Default Credentials which in turn connects using the IAM roles assigned to cloud function.

After editing the source code of a function that was deployed locally using the gcloud sdk, we can re-run the previous command from a terminal to update and redeploy the cloud function.

Now that a connection has been established, we can implement the CREATE-USER case to create a new user using data from the request body and then move on to the LOGIN-USER which finds an existing user and sends back a cookie.

require("dotenv").config();

const { Firestore } = require("@google-cloud/firestore");

const path = require("path");

const { v4 : uuid } = require("uuid")

const cors = require("cors")({ origin: true });

const client = new SecretManagerServiceClient();

exports.firestoreFunction = function (req, res) {

return cors(req, res, () => {

const { email, password, type } = req.body;

const firestore = new Firestore();

const document = firestore.collection("users");

if (!type) {

res.status(422).send("An action type was not specified");

}

switch (type) {

case "CREATE-USER":

if (!email || !password) {

res.status(422).send("email and password fields missing");

}

const id = uuid()

return bcrypt.genSalt(10, (err, salt) => {

bcrypt.hash(password, salt, (err, hash) => {

document.doc(id)

.set({

id : id

email: email,

password: hash,

img_uri : null

})

.then((response) => res.status(200).send(response))

.catch((e) =>

res.status(501).send({ error : e })

);

});

});

case "LOGIN":

break;

default:

res.status(400).send(${type} is not a valid function action)

}

});

};

We generated a UUID using the uuid package to be used as the ID of the document about to be saved by passing it into the set method on the document and also the user’s id. By default, a random ID is generated on every inserted document but in this case, we would update the document when handling the image upload and the UUID is what would be used to get a particular document to be updated. Rather than store the user’s password in plain text, we salt it first using bcryptjs then store the result hash as the user’s password.

Integrating the firestoreFunction cloud function into the app, we use it from the CREATE_USER case within the user reducer.

After clicking the Create Account button, an action is dispatched to the reducers with a CREATE_USER type to make a POST request containing the typed email and password to the firestoreFunction function’s endpoint.

import { createContext } from "react";

import { navigate } from "@reach/router";

import Axios from "axios";

export const userState = {

user : null,

isLoggedIn: false,

};

export const UserReducer = (state, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case "CREATE_USER":

const FIRESTORE_FUNCTION = process.env.REACT_APP_FIRESTORE_FUNCTION;

const { userEmail, userPassword } = action;

const data = {

type: "CREATE-USER",

email: userEmail,

password: userPassword,

};

Axios.post(${FIRESTORE_FUNCTION}, data)

.then((res) => {

navigate("/home");

return { ...state, isLoggedIn: true };

})

.catch((e) => console.log(couldnt create user. error : ${e}));

break;

case "LOGIN-USER":

break;

case "UPLOAD-USER-IMAGE":

break;

case "FETCH-DATA" :

break

case "LOGOUT":

navigate("/login");

return { ...state, isLoggedIn: false };

default:

break;

}

};

export const UserContext = createContext(userState);

Above, we made use of Axios to make the request to the firestoreFunction and after this request has been resolved we set the user initial state from null to the data returned from the request and lastly we route the user to the home page as a logged in user.

Next, we move on to implement a login functionality within our firestoreFunction function to enable an existing user log in to their account using their saved credentials.

require("dotenv").config();

const { Firestore } = require("@google-cloud/firestore");

const path = require("path");

const cors = require("cors")({ origin: true });

const client = new SecretManagerServiceClient()

exports.firestoreFunction = function (req, res) {

return cors(req, res, () => {

const { email, password, type } = req.body;

const firestore = new Firestore();

const document = firestore.collection("users");

if (!type) {

res.status(422).send("An action type was not specified");

}

switch (type) {

case "CREATE":

// ... CREATE - USER LOGIC

break

case "LOGIN":

break;

default:

res.status(500).send({ error : ${type} is not a valid action })

}

});

};

At this point, a new user can successfully create an account successfully and get routed to the home page. This process demonstrates how we use the Cloud Firestore to perform the basic saving and mutation of data in a serverless application.

Handling File Storage

The storing and retrieving of a user’s files in an application is most times a much-needed feature within an application. In an application connected to a node.js backend, Multer is often used as a middleware to handle the multipart/form-data which an uploaded file comes in. But in the absence of the node.js backend, we could use an online file storage service such as the Google Cloud Storage to store files.

The Google Cloud Storage is a globally available file storage service used to store any amount of data as objects for applications into buckets. It is flexible enough to handle the storage of static assets for both small and large-sized applications.

To use the Cloud Storage service within an application, we could make use of the available Storage API endpoints or by using the official node Storage client library. However, the Node Storage client library does not work within a Browser window so we could make use of a Cloud Function where we would use the library.

An example of this, is the Cloud Function below which connects and uploads a file to a created Cloud Bucket.

const cors = require("cors")({ origin: true });

const { Storage } = require("@google-cloud/storage");

const StorageClient = new Storage();

exports.Uploader = (req, res) => {

const { file } = req.body;

StorageClient.bucket("TEST_BUCKET")

.file(file.name)

.then((response) => {

console.log(response);

res.status(200).send(response)

})

.catch((e) => res.status(422).send({error : e}));

});

};

From the cloud function above, we are performing the two following main operations:

First, we create a connection to the Cloud Storage within the

Storage constructorand it uses the Application Default Credentials (ADC) feature on the Google Cloud to authenticate with the Cloud Storage.Second, we upload the file included in the request body to our

TEST_BUCKETby calling the.filemethod and passing in the file’s name. Since this is an asynchronous operation, we use a promise to know when this action has been resolved and we send a200response back thus ending the life-cycle of the invocation.

Now, we can expand the Uploader Cloud Function above to handle the upload of a user’s profile image. The cloud function will receive a user’s profile image, store it within our application’s cloud bucket, and then update the user’s img_uri data within our users' collection in the Firestore service.

require("dotenv").config();

const { Firestore } = require("@google-cloud/firestore");

const cors = require("cors")({ origin: true });

const { Storage } = require("@google-cloud/storage");

const StorageClient = new Storage();

const BucketName = process.env.STORAGE_BUCKET

exports.Uploader = (req, res) => {

return Cors(req, res, () => {

const { file , userId } = req.body;

const firestore = new Firestore();

const document = firestore.collection("users");

StorageClient.bucket(BucketName)

.file(file.name)

.on("finish", () => {

StorageClient.bucket(BucketName)

.file(file.name)

.makePublic()

.then(() => {

const img_uri = https://storage.googleapis.com/${Bucket}/${file.path};

document

.doc(userId)

.update({

img_uri,

})

.then((updateResult) => res.status(200).send(updateResult))

.catch((e) => res.status(500).send(e));

})

.catch((e) => console.log(e));

});

});

};Now we have expanded the Upload function above to perform the following extra operations:

First, it makes a new connection to the Firestore service to get our

userscollection by initializing the Firestore constructor and it uses the Application Default Credentials (ADC) to authenticate with the Cloud Storage.After uploading the file added in the request body we make it public in order to be accessible via a public URL by calling the

makePublicmethod on the uploaded file. According to the Cloud Storage’s default Access Control, without making a file public, a file cannot be accessed over the internet and to be able to do this when the application loads.

Note: Making a file public means anyone using your application can copy the file link and have unrestricted access to the file. One way to prevent this is by using a Signed URL to grant temporary access to a file within your bucket instead of making it fully public.

- Next, we update the user’s existing data to include the URL of the file uploaded. We find the particular user’s data using Firestore’s

WHEREquery and we use theuserIdincluded in the request body, then we set theimg_urifield to contain the URL of the newly updated image.

The Upload cloud function above can be used within any application having registered users within the Firestore service. All that is needed to make a POST request to the endpoint, putting the user’s IS and an image in the request body.

An example of this within the application is the UPLOAD-FILE case which makes a POST request to the function and puts the image link returned from the request in the application state.

# index.js

import Axios from 'axios'

const UPLOAD_FUNCTION = process.env.REACT_APP_UPLOAD_FUNCTION

export const UserReducer = (state, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case "CREATE-USER" :

# .....CREATE-USER-LOGIC ....

case "UPLOAD-FILE":

const { file, id } = action

return Axios.post(UPLOAD_FUNCTION, { file, id }, {

headers: {

"Content-Type": "image/png",

},

})

.then((response) => {})

.catch((e) => console.log(e));

default :

return console.log(`${action.type} case not recognized`)

}

}

From the switch case above, we make a POST request using Axios to the UPLOAD_FUNCTION passing in the added file to be included in the request body and we also added an image Content-Type in the request header.

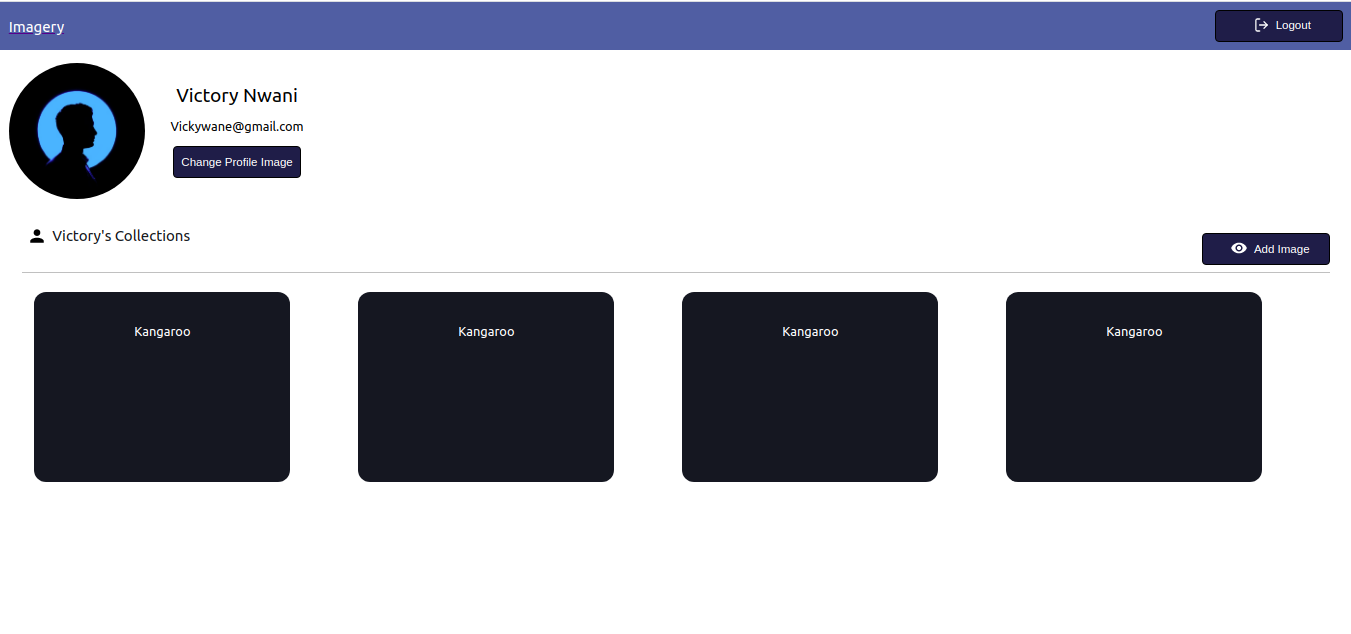

After a successful upload, the response returned from the cloud function would contain the user’s data document which has been updated to contain a valid url of the image uploaded to the google cloud storage. We can then update the user’s state to contain the new data and this would also update the user’s profile image src element in the profile component.

Handling Cron Jobs

Repetitive automated tasks such as sending emails to users or performing an internal action at a specific time are most times an included feature of applications. In a regular node.js application, such tasks could be handled as cron jobs using node-cron or node-schedule. When building serverless applications using the Google Cloud Platform, the Cloud Scheduler is also designed to perform a cron operation.

Note: Although the Cloud Scheduler works similar to the Unix cron utility in creating jobs that are executed in the future, it is important to note that the Cloud Scheduler does not execute a command as the cron utility does. Rather it performs an operation using a specified target.

As the name implies, the Cloud Scheduler allows users to schedule an operation to be performed at a future time. Each operation is called a job and jobs can be visually created, updated, and even destroyed from the Scheduler section of the Cloud Console. Asides from a name and description field, jobs on the Cloud Scheduler consist of the following:

- Frequency: This is used to schedule the execution of the Cron job. Schedules are specified using the unix-cron format which is originally used when creating background jobs on the cron table in a Linux environment. The unix-cron format consists of a string with five values each representing a time point. Below we can see each of the five strings and the values they represent.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - minute ( - 59 )

| - - - - - - - - - - - - - hour ( 0 - 23 )

| | - - - - - - - - - - - - day of month ( 1 - 31 )

| | | - - - - - - - - - month ( 1 - 12 )

| | | | - - - - - -- day of week ( 0 - 6 )

| | | | |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| | | | |

* * * * * The Crontab generator tool comes in handy when trying to generate a frequency-time value for a job. If you are finding it difficult to put the time values together, the Crontab generator has a visual drop-down where you can select the values that make up a schedule and you copy the generated value and use as the frequency.

Timezone: The timezone from where the cron job is executed. Due to the time difference between time-zones, cron jobs executed with different specified time-zones would have different execution times.

Target: This is what is used in the execution of the specified Job. A target could be an

HTTPtype where the job makes a request at the specified time to URL or a Pub/Sub topic which the job can publish messages to or pull messages from and lastly an App Engine Application.

The Cloud Scheduler combines perfectly well with HTTP triggered Cloud Functions. When a job within the Cloud Scheduler is created with its target set to HTTP, this job can be used to executed a cloud function. All that needs to be done is to specify the endpoint of the cloud function, specify the HTTP verb of the request then add whatever data needs to be passed to function in the displayed body field. As shown in the sample below:

The cron job in the image above would run by 9 AM every day making a POST request to the sample endpoint of a cloud function.

A more realistic use case of a cron job is sending scheduled emails to users at a given interval using an external mailing service such as Mailgun. To see this in action, we will create a new cloud function which sends a HTML email to a specified email address using the nodemailer JavaScript package to connect to Mailgun,

# index.js

require("dotenv").config();

const nodemailer = require("nodemailer");

exports.Emailer = (req, res) => {

let sender = process.env.SENDER;

const { reciever, type } = req.body

var transport = nodemailer.createTransport({

host: process.env.HOST,

port: process.env.PORT,

secure: false,

auth: {

user: process.env.SMTP_USERNAME,

pass: process.env.SMTP_PASSWORD,

},

});

if (!reciever) {

res.status(400).send({ error: Empty email address });

}

transport.verify(function (error, success) {

if (error) {

res

.status(401)

.send({ error: failed to connect with stmp. check credentials });

}

});

switch (type) {

case "statistics":

return transport.sendMail(

{

from: sender,

to: reciever,

subject: "Your usage satistics of demo app",

html: { path: "./welcome.html" },

},

(error, info) => {

if (error) {

res.status(401).send({ error : error });

}

transport.close();

res.status(200).send({data : info});

}

);

default:

res.status(500).send({

error: "An available email template type has not been matched.",

});

}

};Using the cloud function above we can send an email to any user’s email address specified as the receiver value in the request body. It performs the sending of emails through the following steps :

- It creates an SMTP transport for sending messages by passing the

host,userandpasswhich stands for password, all displayed on the user’s Mailgun dashboard when a new account is created. - Next, it verifies if the SMTP transport has the credentials needed in order to establish a connection. If there’s an error in establishing the connection, it ends the function’s invocation and sends back a

401 unauthenticatedstatus code. - Next, it calls the

sendMailmethod to send the email containing the HTML file as the email’s body to the receiver's email address specified in thetofield.

Note: We use a switch statement in the cloud function above to make it more reusable for sending several emails for different recipients. This way we can send different emails based on the type field included in the request body when calling this cloud function.

Now that there is a function that can send an email to a user; we are left with creating the cron job to invoke this cloud function. This time the cron jobs would be created dynamically each time a new user is created using the official Google cloud client library for the Cloud Scheduler from the initial firestoreFunction.

We expand the CREATE-USER case to create the job which sends the email to the created user at a one-day interval.

require("dotenv").config();cloc

const { Firestore } = require("@google-cloud/firestore");

const scheduler = require("@google-cloud/scheduler")

const cors = require("cors")({ origin: true });

const EMAILER = proccess.env.EMAILER_ENDPOINT

const parent = ScheduleClient.locationPath(

process.env.PROJECT_ID,

process.env.LOCATION_ID

);

exports.firestoreFunction = function (req, res) {

return cors(req, res, () => {

const { email, password, type } = req.body;

const firestore = new Firestore();

const document = firestore.collection("users");

const client = new Scheduler.CloudSchedulerClient()

if (!type) {

res.status(422).send({ error : "An action type was not specified"});

}

switch (type) {

case "CREATE-USER":

const job = {

httpTarget: {

uri: process.env.EMAIL_FUNCTION_ENDPOINT,

httpMethod: "POST",

body: {

email: email,

},

},

schedule: "/30 /6 */5 10 4",

timezone: "Africa/Lagos",

}

if (!email || !password) {

res.status(422).send("email and password fields missing");

}

return bcrypt.genSalt(10, (err, salt) => {

bcrypt.hash(password, salt, (err, hash) => {

document

.add({

email: email,

password: hash,

})

.then((response) => {

client.createJob({

parent : parent,

job : job

}).then(() => res.status(200).send(response))

.catch(e => console.log(unable to create job : ${e}) )

})

.catch((e) =>

res.status(501).send(error inserting data : ${e})

);

});

});

default:

res.status(422).send(${type} is not a valid function action)

}

});

};

From the snippet above, we can see the following:

- A connection to the Cloud Scheduler from the Scheduler constructor using the Application Default Credentials (ADC) is made.

- We create an object consisting of the following details which make up the cron job to be created:

uri

The endpoint of our email cloud function which a request would be made to.body

This is the data containing the email address of the user to be included when the request is made.schedule

The unix cron format representing the time when this cron job is to be performed.

- After the promise from inserting the user’s data document is resolved, we create the cron job by calling the

createJobmethod and passing in the job object and the parent. - The function’s execution is ended with a

200status code after the promise from thecreateJoboperation has been resolved.

After the job is created, we would see it listed on the scheduler page.

From the image above we can see the time scheduled for this job to be executed. We can decide to manually run this job or wait for it to be executed at the scheduled time.

Conclusion

Within this article, we have had a good look into serverless applications and the benefits of using them. We also had an extensive look at how developers can manage their serverless applications on the Google Cloud using Cloud Functions so you now know how the Google Cloud is supporting the use of serverless applications.

Within the next years to come, we will certainly see a large number of developers adapt to the use of serverless applications when building applications. If you are using cloud functions in a production environment, it is recommended that you read this article from a Google Cloud advocate on “6 Strategies For Scaling Your Serverless Applications”.

The source code of the created cloud functions are available within this Github repository and also the used frontend application within this Github repository. The frontend application has been deployed using Netlify and can be tested live here.

References

- Google Cloud

- Cloud Functions

- Cloud Source Repositories

- Cloud Scheduler overview

- Cloud Firestore

- “6 Strategies For Scaling Your Serverless Applications,” Preston Holmes