Developing For The Semantic Web

In July the Wikimedia Foundation announced Abstract Wikipedia, an attempt to markup knowledge that is language-independent. In many respects, this is the culmination of decades of buildup, during which the dream of a Semantic Web has never quite taken off, but never quite disappeared either.

As a matter of fact the Semantic Web is growing, and as it renews its mission we all stand to gain from incorporating semantic markup into our websites, be they personal blogs or social media giants. Whether you care about sophisticated web experiences, SEO, or fending off the tyranny of web monopolies, the Semantic Web deserves our attention.

The benefits of developing for the Semantic Web are not always immediate, or visible, but every site that does strengthens the foundations of an open, transparent, decentralized internet.

The Semantic Web

What exactly is the Semantic Web? It is a machine-readable web, providing through metadata “a common framework that allows data to be shared and reused across application, enterprise, and community boundaries."

The idea is as old as the World Wide Web itself. Older, in fact. It was a focal point of Tim Berners-Lee's 1989 proposal. As he outlined, not only should documents form webs, but the data inside them should too:

The Semantic Web’s tread a rocky road in the decades since. Since the turn of the millennium, it has morphed into multiple concepts — open data, knowledge graphs — all effectively meaning the same thing: webs of data.

As the W3C summarises, it is “an extension of the current web in which information is given well-defined meaning, better-enabling computers and people to work in cooperation."

The idea has had its fair share of advocates. Internet hacktivist Aaron Swartz wrote a book manuscript about the Semantic Web called A Programmable Web. In it he wrote:

“Documents can’t really be merged and integrated and queried; they serve mostly as isolated instances to be viewed and reviewed. But data are protean, able to shift into whatever shape best suits your needs.”

For a variety of reasons, the Semantic Web has not taken off in the same way the Web has, though it is catching up. Several markups have tried to seize the mantle over the years — RDFa, OWL, and Schema to name a few — though none have become standard in the way, say, HTML or CSS have. The barrier to entry was too high.

However, the dream of the Semantic Web has endured, and as more and more sites incorporate it into their designs there’s all the more reason to join the party. The more sites that get on board, the stronger the Semantic Web becomes.

Further Reading

- Data Intelligence

- The Semantic Web, a 2001 article by Tim Berners-Lee, James Hensley, and Ora Lassila

- Credible Web Community Group at W3C

Knowledge Without Borders

Before getting into the weeds of how to design for the Semantic Web, it’s worth digging a little deeper into the why. What does it matter whether data is connected? Aren’t connected documents enough?

There are several reasons why the Semantic Web continues to be pushed by those who care about a free and open internet. Understanding those reasons is essential to the implementation process. It shouldn’t be a case of ‘eat your vegetables, use semantic markup.’ The Semantic Web is something to believe in and be a part of.

Benefits of the Semantic Web include:

- Richer, more sophisticated web experiences

- Bypassing content silos and internet monopolies

- Improved search engine readability and rankings

- Democratisation of information

Most of these can be traced back to a core tenet of the Semantic Web: a universal language for data. Although the internet has already done wonders for international communication, there’s no escaping the fact some countries have it much better than others. Take languages used on the web vs. languages used in the real world, for example. The eagle-eyed among you may be able to spot a slight imbalance in the data below...

The borderless utopia of the web is not as close as it might seem to those of us inside the English-speaking bubble. Is that something to chastise anyone for? Not necessarily, but it is something to face up to. Doing so highlights the importance of markup that bridges those gaps. By enriching the data of the web, we take the strain off of its languages.

This is the crux of the recently announced Abstract Wikipedia, which will attempt to decouple articles from the language they happen to be written in. Wikimedia Executive Director Katherine Maher writes: “Using code, volunteers will be able to translate these abstract ‘articles’ into their own languages. If successful, this could eventually allow everyone to read about any topic in Wikidata in their own language.”

Abstract Wikipedia creator Denny Vrandečić has been a Semantic Web advocate for years, recognizing its potential to unlock untapped potential online. Breaking down national barriers is essential to that process.

“No matter what language you publish your content in, you are going to miss out on including the vast majority of people in the world. The Web gave us this wonderful opportunity to have global reach — but by relying on a single language, or a small set of languages, we are squandering this opportunity. While the most important objective is to create good content in the first place, you invite more people to participate in the development of better content by being language-independent. It helps you lower the barriers to contribution and consumption, and it allows for many more people to benefit from that effort.”

— Denny Vrandečić, Abstract Wikipedia creator

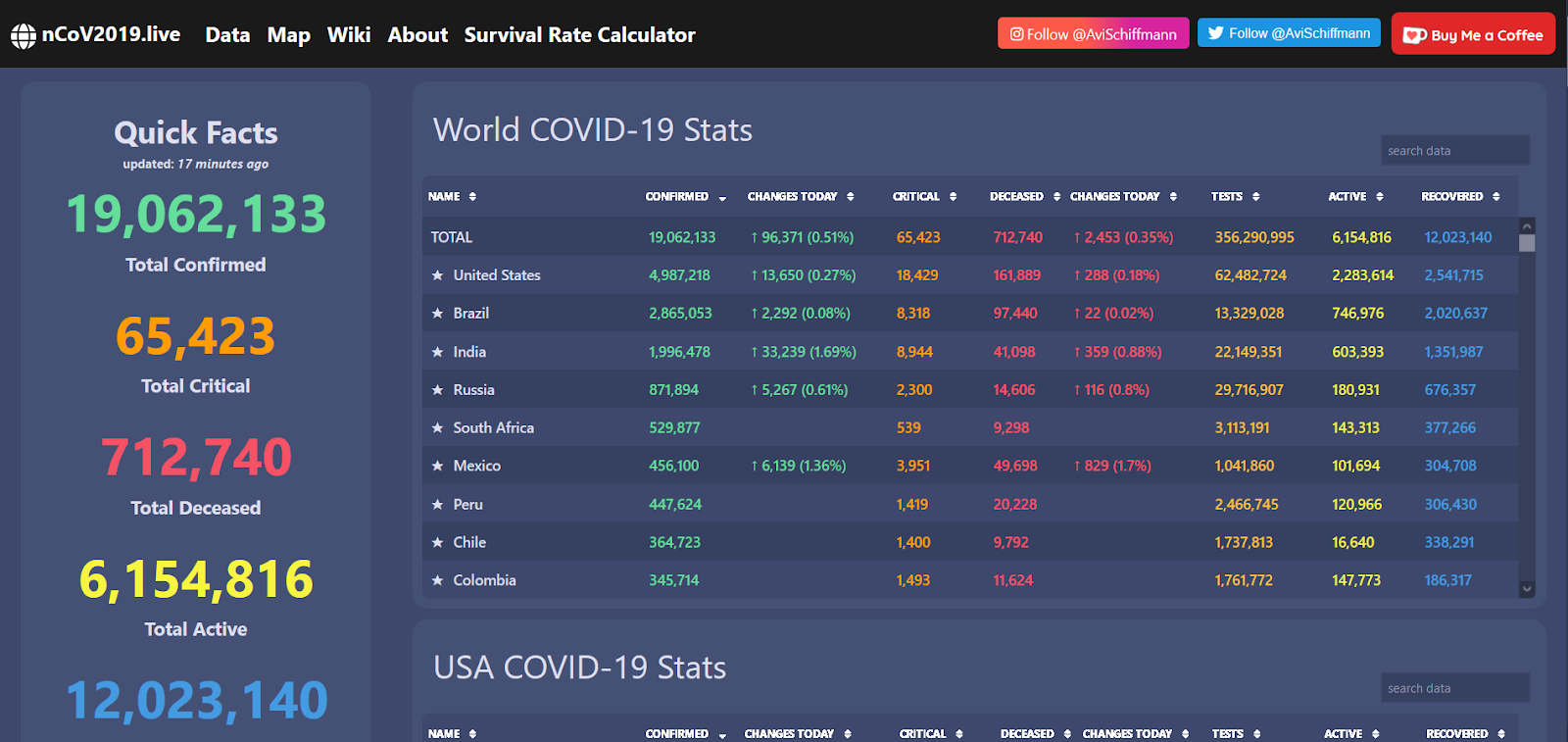

A timely example of this has been data visualization during the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus has wreaked unspeakable havoc worldwide, but it has also been a shining moment for open data networks, allowing superb web apps, reporting, and more to be common across the web.

And of course, when data is transparent and easily accessible, it makes it easier to identify anomalies… or straight up deceit. Widespread public access to the kind of information above would be unthinkable even 20 years ago. Now we expect it, and smell a rat when it’s denied us. Data is powerful, and if we want to, can be wielded for good.

Similarly, checking ourselves out of content silos — a hallmark of the modern web experience — takes power away from web monopolies like Google, Facebook, and Twitter. We’re so used to third party platforms deciphering and presenting information that we forget they’re not strictly necessary.

“If we had shared formats, shared protocols, we might still end up with certain providers playing a large role in certain markets — think of Gmail for email — but everyone is free to move to another provider, and the market remains competitive.”

— Denny Vrandečić, Abstract Wikipedia creator

The Semantic Web is silo-less; it is free, open, and abstract, enabling communication between different languages and platforms that would be far more difficult otherwise.

Data-fying Online Content

Designing for the Semantic Web boils down to data-fying online content — looking at your content and seeing what can (and should) be abstracted. What does this mean in practical terms, beyond vaguely agreeing it’s a worthwhile thing to do? It depends:

- If starting a project from scratch, incorporate Semantic Web considerations into what you do. As a website takes shape, weave semantic markup into its DNA.

- If updating or rebuilding a project, assess what could be woven into the Semantic Web that currently isn’t, then implement.

Both cases basically amount to data-fying content. In this section, we will go through some examples of data abstraction and how it can make content better, smarter, and more widely available.

Abstracting Information

Designing and developing for the Semantic Web means looking at online content with your data hat on. Most of us experience the web as a series of connecting documents or pages; what you want to do with the Semantic Web is connect information. This means assessing your content for data points then adjusting the design based on what you find.

Semantic Web advocate James Hendler outlines this process particularly well with his DIVE ethos. (DIVE into the data, eh? Eh?). It breaks down as follows:

- Discover

Find datasets and/or content (including outside your own organization). - Integrate

Link the relations using meaningful labels. - Validate

Provide inputs to modeling and simulation systems. - Explore

Develop approaches to turn data into actionable knowledge.

Developing for the Semantic Web is largely about having that birds-eye view of the things you make, and how it potentially feeds into infinitely richer web experiences. As Hendler says, actionable knowledge is the goal.

This really can be applied to almost any type of web content, but let’s start with a common example: recipes. Let’s say you run a cooking blog, with new recipes every Thursday. If you’re French and post a smashing soufflé recipe on your personal blog in plain text, it’s only useful to those who can read French.

However, by implementing semantic markup the blog can be transformed into a machine-readable recipe data set. Syntax exists for cooking terms to be abstracted. Schema, for example, which can work alongside Microdata, RDFa, or JSON-LD, has markup including:

- prepTime

- cookTime

- recipeYield

- recipeIngredient

- estimatedCost

- nutrition, breaking down into calories and fatContent

- suitableForDiet.

I could go on. The full range of options, with examples, can be read at Schema.org. In adding them to the post format the format of the recipe needn’t change at all — you’re simply putting the information in terms computers can understand.

For example, everything highlighted blue in the BBC recipe above has also been given semantic markup — from cooking time to nutritional content. You can see what’s going on under the hood by entering the recipe URL into Google’s Rich Results Test. Note the ‘Add to shopping list’ functionality, an example of connection made possible by Semantic Web implementation. Good content becomes usable data.

Most of us have crossed paths with this kind of sophistication via search results, but the applications are much wider than that. Semantic markup of recipes makes it easier for websites to be found and used by home assistants. Listed ingredients can be ordered from the local supermarket. Recipes could be filtered in all sorts of ways — for diets, allergies, religion, cost, you name it. Or let's say you had a limited number of ingredients in the house. With a database you could input those ingredients and see what recipes fit the bill.

The range of possibilities really do border on limitless. As Swartz said, data is protean. Once you have it you can use it in all sorts of weird and wonderful ways. This piece is not about those weird and wonderful ways so much as it is about making them possible. Designing for the Semantic Web makes subsequent design infinitely richer.

Here’s a more personal example to show what I mean. A couple of friends and I run a little music webzine as a hobby. Though we publish the odd article or interview, the ‘main event’ is our weekly album reviews, in which the three of us each assign a score, choose favorite tracks, and write summaries. We’ve been going for more than five years, which means we have close to 250 reviews, which means an awful lot of potential data. We didn’t realize how much until we started redesigning the site.

I touched upon this in a piece about baking structured data into the design process. In dissecting our reviews we realized they were chock full of information that could be given semantic markup. Artists, album names, artwork, release date, individual scores, overall scores, release type, and more. What’s more — and this is where it gets really exciting — we realized we could connect to an existing database: MusicBrainz.

This two-way approach is the crux of the Semantic Web. When our music website relaunches it will be its own open data source with thousands of unique data points. Connecting to an existing music database will give our own data more context — and potential. Thousands of data points becomes tens of thousands of data points, maybe more.

The graphic above only scratches the surface of how much information will be connected to reviews pages. The content is the same as it was before, only now it is plugged into a metadata ecosystem — the Giant Global Graph, as Berners-Lee once called it.

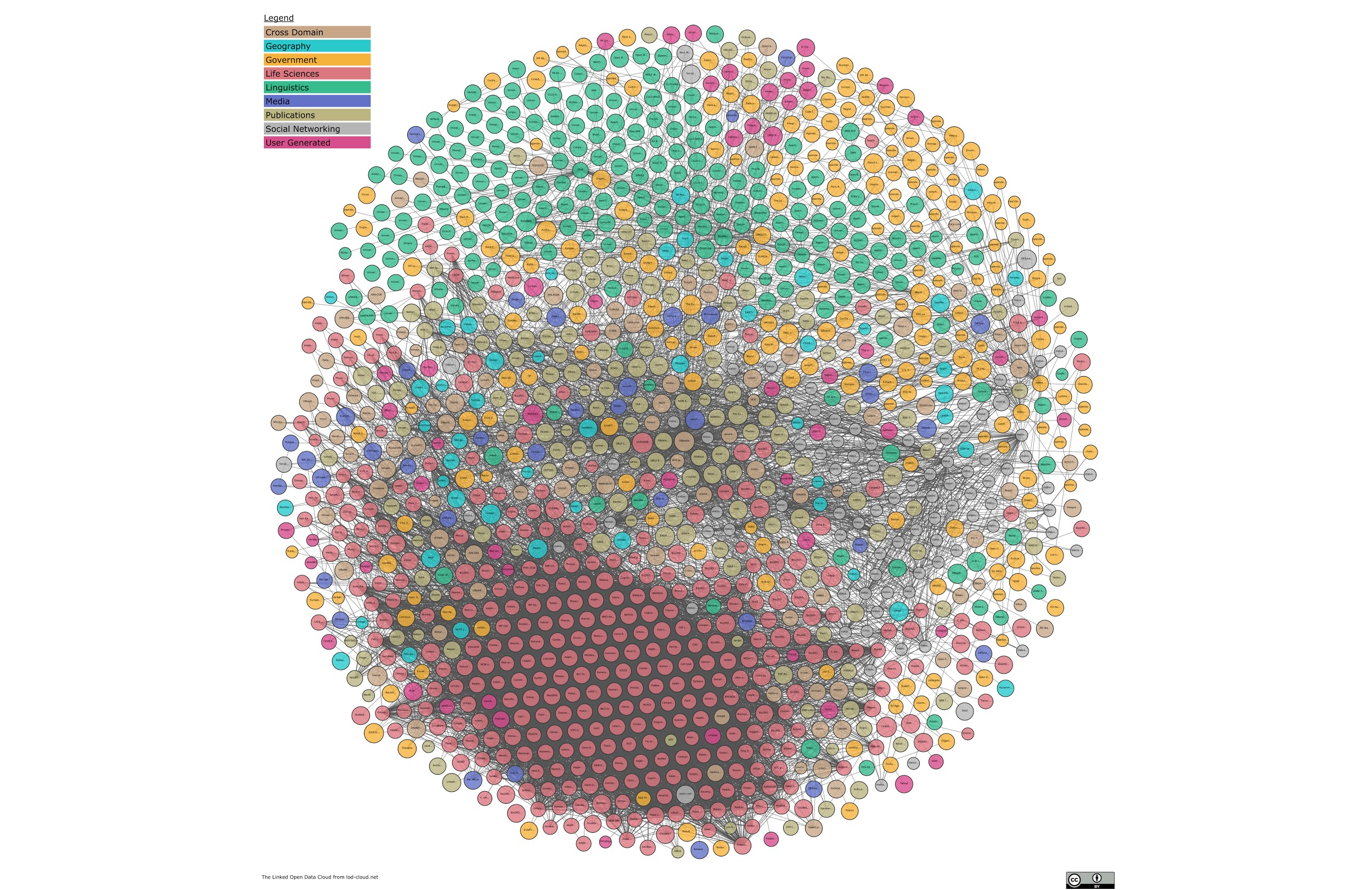

Developing for the Semantic Web means identifying your own data, markup it up, then sussing out how it connects to other data. Because it does. It always does. And that process is how this…

… in time becomes this…

The second image is The Linked Open Data Cloud, a constantly updating visualization of the web’s connected data. That red hive of connections is the sciences; the rest has some way to go. That’s where we come in.

Useful Semantic Web Resources

- RDF at w3schools.com

- W3C’s RDF validator

- “The Semantic Web Made Easy” by W3C

- “Whatever Happened to the Semantic Web?” by Two-Bit History

- JSON-LD generator

- Google’s Structured Data Markup Helper

Plugging In

The ideal of the Semantic Web is connection. Make data, share data, demand data. Be part of an information ecosystem. When you’re creating original data, great. Share it. When data already exists and you’d like to use it, pull it in.

Here are just a handful of the data resources out there:

- DPpedia

- MusicBrainz

- WorldCat

- ISBNdb

Indeed, where databases like these exist, I’d go so far as to say the right thing to do would be update them where they’re lacking information. Why keep it to yourself? Become a contributor, a Semantic Web advocate.

Implementation

As far as building Semantic Webness into your sites goes, I’m certainly not advocating manual, doc-by-doc markup. Who’s got time for that? More often than not the solution is a case of standardizing a format and templating for it.

Templating is the big opportunity here. How many people really have time to markup all that information manually? However, if you have custom inputs, you get the best of both worlds. Content can be filled with people-friendly information and the information exists as data ready to serve whatever purpose comes to mind.

Take, for example, a static site generator like Eleventy, which has been enjoying a bit of a love-in from the dev community lately. You write a post, run it through a template, and you’re golden. So why not incorporate semantic markup into the template itself?

Like Eleventy, the new version of our music webzine site uses Markdown for its posts. While we have the same old text posts we always did, every review now also includes the following metadata inputs, which are then pulled into the template:

Together with author details in the body of the post and some generic website info, this then translates to the following semantic markup:

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "http://schema.org/",

"@type": "Review",

"reviewBody": "One of the definitive albums released by, quite possibly, the greatest singer-songwriter we've ever seen. To those looking to probe Young's daunting discography: start here.",

"datePublished": "2020-08-14",

"author": [{

"@type": "Person",

"name": "André Dack"

},

{

"@type": "Person",

"name": "Frederick O'Brien"

},

{

"@type": "Person",

"name": "Marcus Lawrence"

}],

"itemReviewed": {

"@type": "MusicAlbum",

"name": "After the Gold Rush",

"@id": "https://musicbrainz.org/release-group/b6a3952b-9977-351c-a80a-73e023143858",

"image": "https://audioxide.com/images/album-artwork/after-the-gold-rush-neil-young.jpg",

"albumProductionType": "http://schema.org/StudioAlbum",

"albumReleaseType": "http://schema.org/AlbumRelease",

"byArtist": {

"@type": "MusicGroup",

"name": "Neil Young",

"@id": "https://musicbrainz.org/artist/75167b8b-44e4-407b-9d35-effe87b223cf"

}

},

"reviewRating": {

"@type": "Rating",

"ratingValue": 27,

"worstRating": 0,

"bestRating": 30

},

"publisher": {

"@type": "Organization",

"name": "Audioxide",

"description": "Independent music webzine founded in 2015. Publishes reviews, articles, interviews, and other oddities.",

"url": "https://audioxide.com",

"logo": "https://audioxide.com/logo-location.jpg",

"sameAs" : [

"https://facebook.com/audioxide",

"https://twitter.com/audioxide",

"https://instagram.com/audioxidecom"

]

}

}

</script>Where before there was just text, on every single review page there will now also be machine-readable versions of what readers see when they visit the site. The words are all still there, the content has barely changed at all — it’s just been data-fyed. From rich search results to interactive review statistics pages, this massively increases what’s possible. The road ahead is wide and open. It also gives us a stake in MusicBrainz’s future. By connecting their data to our own data, we in turn want to see it do well, and will do our part to ensure it does.

The appropriate semantic markup depends on the nature of a website, but odds are it exists. Start with the obvious inputs (date, author, content type, etc.) and work your way into the weeds of the content. The first step could be as simple as a hCard (a kind of digital ID card) for your personal website. Print out screenshots of pages and start annotating. You’ll be amazed by how much content can be data-fyed.

Beyond Imagination

Designing and developing for the Semantic Web is a practice that dates back to the Internet’s founding ideals. Whether you value beautiful, informative data visualization, want more sophisticated search results, wish to remove power from web monopolies, or simply believe in free and open information, the Semantic Web is your ally.

Aaron Swartz closed his manuscript with a call to hope:

“The Semantic Web is based on bet, a bet that giving the world tools to easily collaborate and communicate will lead to possibilities so wonderful we can scarcely even imagine them right now.”

Abstract Wikipedia Denny Vrandečić echoes those sentiments today, saying:

“There’s a need for a web infrastructure that will facilitate interoperability between services, which requires a common set of standards for representing data, and common protocols across providers.”

The Semantic Web has limped along long enough for it to be clear that a silver bullet language is unlikely to appear, but there are enough now peacefully coexisting for Berners-Lee’s founding dream to be a reality for most of the web. Each of us can be advocates in our own neighborhoods.

Be Better, Demand Better

As Tim Berners-Lee has said, the Semantic Web is a culture as much as it is a technical hurdle. In a 2009 TED Talk he summed it up nicely: make linked data, demand linked data. That’s truer now than ever. The World Wide Web is only as open and connected and good as we force it to be. Whenever you make something online ask yourself, “How can this plug into the Semantic Web?” The answers will add new dimensions to the things we create, and create unimaginably wonderful new possibilities for years to come.