Better Documentation And Team Communication With Product Design Docs

The typical process for working as a product designer in a company or startup could be familiar to you: a new product is being developed for which to provide a design solution. Then you work on some design proposals and you pitch them in front of 1–3 people to gather feedback.

Sometimes this process works just fine, but some other times it doesn’t. For instance, some people are busy paying attention to finish their own tasks and do not spend enough time to provide clear and concise feedback for your design proposal.

It may also happen that even though your process is good you still want to formalize the process by writing down decisions, keeping track of iterations, and the design process in general, especially in the current times where we find ourselves working remotely due to COVID19.

Documenting the process has many benefits. For example, it makes your work more visible, creates opportunities to get feedback from many more people, improves the overall communication, and provides a clear picture of how a feature was designed with all the context and considerations around.

The Fall Of The Hero Designer

Around 2018, I was working as a remote Product Designer from Madrid in a company that operates in Latin America, involving in this process other teams from México and São Paulo, Brazil.

Before I started working at this company, I had plenty of different experiences in my career working in small and big-sized environments from many different sectors like news media, design studios, a social network, a mobile OS, founded an e-grocery startup, and even did some freelance gigs with other small startups.

During those years I had been following the same approach, you get some people sitting in the same room, pitch your solution, provide some screens, flows, get some feedback, and present it again. After some iterations, your work will be ready to reach the development phase.

However, this very same approach stopped working. Shortly after joining the team, I realized that just pitching my designs on a video call wasn’t enough. I was creating a lot of proposals, but I couldn’t reach final approval from my stakeholders and teammates. I was confused and kept asking myself: What was happening? Wasn’t I designing the best solution possible? Wasn’t I delivering good quality work? Every one of those questions was making me lose confidence in myself. The problem was that I needed to adapt my process to this environment.

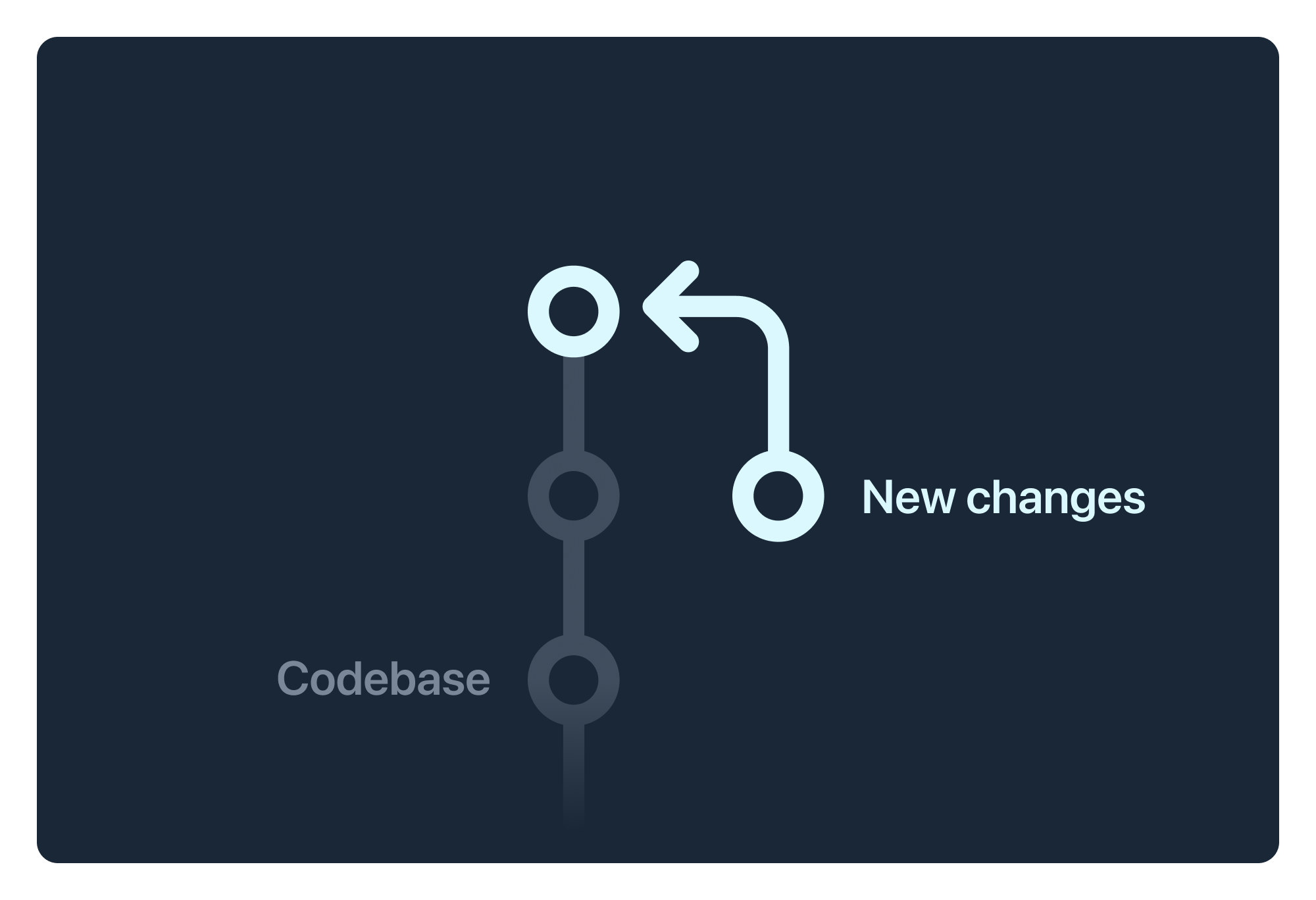

As soon as I realized that my process wasn’t working, I started reading a lot of articles about how to work as a designer remotely, the seagull effect (when someone comes into your work, harshly criticizes it and then flies away), how other companies were approaching remote collaboration, and how they formalized their process by writing it down. After reading all this material, I wondered how developers were facing this same issue? How do they collaborate on remote environments in an almost asynchronous manner? How do they come to final agreements? I discovered that in fact, the developer community already has a process that works quite well for them: It is called pull requests.

Pull requests let you introduce changes in a larger codebase by documenting them and validate your decisions with other people's feedback. In this way, the changes you introduce mix perfectly with all the standards and connections the code already has in place. This is exactly what I needed to achieve, but of course in a design-fashion approach. Let me introduce you to the Product Design Doc.

The Product Design Doc

A Product Design Doc (PDD), is a document that converts the problems you want to solve, the context, and the final solution into an iteration or stage-based approach.

This means you can document your entire design process into a single document that can be shared with anyone at your company and it will live as a knowledge base for the product decisions you make. Sounds cool uh? Let’s dig into the details:

Overall Concepts

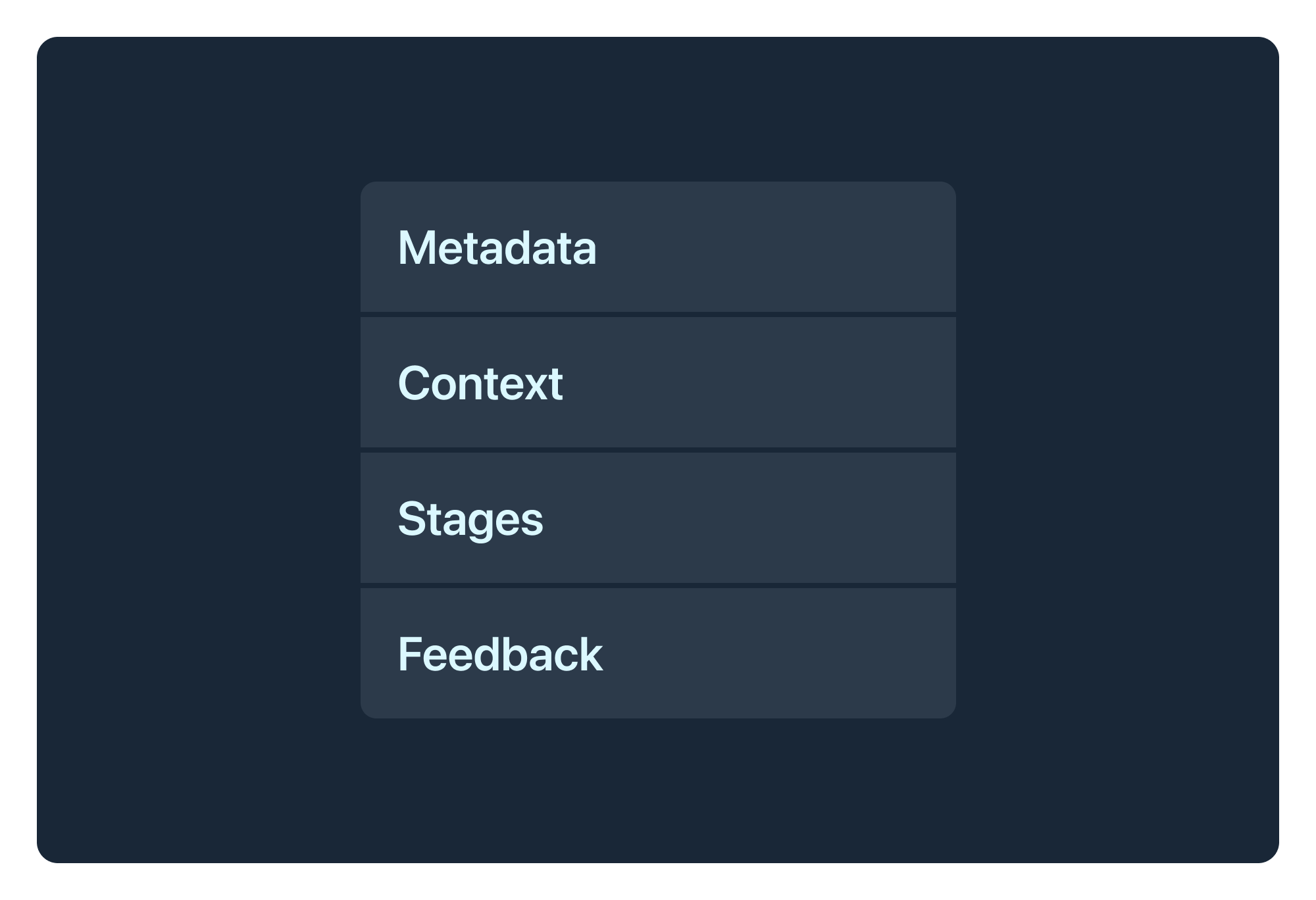

A PDD can be described in 4 major concepts: Metadata, Context, Stages, and Feedback.

Metadata is just useful information about the document such as the title, date, status, and so on.

Context is what other people need to read, for understanding the design proposals you make, think about it like the description, problem, abstract, or goals of what you need to achieve.

Stages are the different iterations of your design, commonly starting focusing on the broader solution and in each stage focusing on more specific details. Each stage is based on the previous and addresses the feedback received. This is a structured way of reaching a final point where resolved issues can not appear again.

Feedback refers to all the opinions, comments, requests, and recommendations you gather from other people. You can gather feedback from your stakeholders or team members.

With these four concepts, you can create different variations of PDD for suiting your needs, every company/project is different and what worked for me, doesn’t have to work in the same way for you. But if you cover these 4 main concepts in your PDD, it will be likely to work in almost any situation.

Example Structure

After understanding the main concepts, I will share with you the structure that I've been using during my time in that company. It has the following sections:

- The Title should be concise, clear and easily distinguished from other PDD titles you already have.

- The Status indicates in which stage is your document right now:

- Draft

Still working on defining the Context. Not ready for feedback. - S30, S60, S90

The different stages (30%, 60%, 90%) of your solution (more details about the stages later). - Complete

All Feedback has been addressed and there are no missing points. The PDD is finished. - The Abstract is the description of the problem you need to design for, commonly linking to other helpful related readings you might have.

- Goals are the key points your solution needs to focus on, this is a checklist that you will be constantly reviewing to be sure you are on the right track.

- S30 (or Stage 30%) is the first proposal you make based on the abstract and the goals, focusing on the broader solution instead of the details, maybe by providing a low fidelity wireframe or similar technique. This is the stage where the solution proposed could take a totally different approach and major feedback is expected to happen.

- S60 (or Stage 60%) is your solution at 60% of completeness and applies the feedback from S30. It has fewer details than S90, but clearly indicates the intention of your solution. You provide a high-fidelity wireframe with more cases involved and some flow definitions. You might receive some sort of feedback mostly focusing on missed cases and small unexpected scenarios.

- S90 (or Stage 90%) is the stage that has the solution at the 90% of completeness and applies the feedback from S60. This stage is focused on the very finest details of your design, including all different scenarios, corner cases, visual design, and even prototypes. It's expected to have some kind of minor feedback.

You might be asking yourself, do I need to follow the same order and stages naming convention? Well, no you don’t. You can rename the stage from S30, S60 and S90 to just: Exploration, Proposal, Solution.

You can also change the ordering so the most refined work (S90, Solution) gets at the top of the document and the reading flow goes from the final stage to the early one (S30, Exploration).

Templates

Start quickly with one of the provided templates for the most common writing platforms. Remember: The naming conventions of the sections are totally customizable. If you don’t like Abstract, just use Brief, About or anything that suits your needs. The main concept you will need to keep is about creating different iterations to focus on each stage, you can just rename S30 by Exploration, S60 by Proposal, and S90 by Solution.

- Paper

- Notion

- Google Docs

- Real-life example

Key Benefits Of Using PDD

Every decision is documented.

Meaning that even when you leave your company/project (and that will happen sooner or later), all the knowledge generated around will stick in the company forever, so other people can look at it and iterate from where you left.Improves communication.

Getting different people from your team on the PDD to provide feedback helps everyone stay on the same page and being aware of the decisions made.Limits endless changes from stakeholders.

Every stage focuses on a different angle of the problem, going from wider solutions to narrow ones. This allows people to focus on a single problem at a time, helping them in the closing stages.The product is built collaboratively.

Instead of the stakeholders defining specific solutions, we let engineering, design, and other teams engage with the solution making them part of it.

Final Notes

Closing the story about this remote company, I got to work there for some more months and I was able to implement the Product Design Docs at least on 5 different projects. My frustration was reduced a lot and I was able to reach a consensus on my design proposals so the product continued to evolve. Since then, the company has grown a lot and some of the work I did during my time is still being used.

PS: I started writing this article in 2019, then in 2021 I saw that Abstract was creating a product for documenting the design process, so I decided to get back on track and finish it. Looks like it’s still quite a relevant topic.

Bibliography

- How to Run Design Exercises on a Remote Team by Hannah Hearth

- Avoid The Seagull Effect: The 30/60/90 Framework For Feedback by Lauren Moon

- How do you design a design doc? by John Saito

- The power of the design doc by Brendan Fagan

- Introducing Notebooks by Matt Colyer