Designing A Better Carousel UX

Carousels don’t have a good reputation, and rightfully so. They have plenty of accessibility issues, they often exhibit low click-through rates, can be very disruptive when auto-advancing and people frequently scroll past through them. Add to it small progress dots with tiny tap areas, barely visible labels and a bit of parallax, and you have a quite troublesome design pattern in your hands.

Yet somehow carousels still manage to find their way to websites and applications. They often make a quite lavish appearance in image galleries and news items, on landing pages and on corporate websites — and especially for onboarding, testimonials, and product highlights.

Carousels come in various sizes and flavors. A wonderful illustration by Jacky Gilbertson (Large preview)

Carousels come in various sizes and flavors. A wonderful illustration by Jacky Gilbertson (Large preview)

What should we keep in mind if we do need to design a carousel? How do we create a better carousel experience that helps people, rather than frustrates them? And how do we avoid common accessibility and usability failures that carousels usually entail? That’s exactly what this article is all about.

Table of Contents

The article is slightly lengthier as expected, so tighten up your seat belts — it’s going to be quite a journey.

- Do Users Actually Use Carousels?

- Scrolling Direction

- Replace Progress Dots with Labels

- Replace Progress Dots With A Horizontal Slider

- Indicate The Current Position

- Prev/Next Buttons

- How Far Should Prev/Next Buttons Jump?

- Keep Prev/Next Buttons Close

- Combine Tabs and Carousels

- Use Thumbnails Or Icons

- Dragging Alone Isn't Good Enough

- Add An Information Scent

- Add At Least 5–7s Delay

- Always Include A "Pause" Button

- Alternatives to Carousels

That’s a very fair question, and quite frequently the answer will be: not really. In fact, it’s almost as if some users were allergic towards carousels. It’s common to see people noticing them, just to make sure they can dismiss them during the entire session. Not many people connect anything relevant with carousels since most of the time the content hidden in the carousel is either irrelevant or promotional — or annoying and distracting.

That’s not very surprising given how large some carousels actually are, sometimes taking up anything between 50 to 90% of the entire screen. And because the content displayed in the carousels is rarely a reason why users end up on the site, it’s dismissed almost instinctively. Hence, users rarely click through the slides of carousels, especially if the very first slide isn’t enticing enough or has no connection with the task at hand.

Carousels definitely won’t help with drawing more attention to general promotions, internal news, or press releases which don’t get much interest anyway. Many higher education websites, public services and online banking (for example) would probably benefit from removing carousels, rather than adding them in.

Auto-advancing carousels don’t solve the issues listed above either. Whenever any portion of the content on the page starts moving, many users will ignore it almost immediately. If you are lucky, users might be trapped exploring relevant content near the carousel, so they might get a glimpse of the second or third slide, but they will bundle all their strengths to ignore it until they move on to the next page.

More often though many people tend to just scroll past auto-advancing carousels, trying to get it out of the view and move on with their task. This is especially noticeable with onboarding tutorials in mobile apps, where the very first thing that users search for when facing an onboarding carousel is a precious “skip” button.

Carousels are also a poor choice when it comes to content discovery. If something important is presented in one of the later slides of a carousel, a vast majority of users will experience severe issues discovering it. Not surprising: if something is important, we should probably not hide it — this goes for the carousel just like it goes for the infamous hamburger navigation.

Finally, carousels also pose severe accessibility issues for keyboard and screen reader users who simply can’t use them properly without thorough development work.

Does it mean that we should dismiss carousels for good and always abandon them at all costs? Not necessarily.

Carousels can be quite effective, especially when we want to highlight all features or options, but lack space to display them all at once. There are a few contexts in which carousels perform fairly well though. This holds true especially if a carousel is meaningfully integrated into a task that a user is trying to complete. In such cases, click-through rates are usually relatively high: users advance carousels at a roughly linear rate.

Carousels work when:

- users are exploring an appropriate option, or choose a pricing plan,

- users browse through testimonials, reviews, products or their features,

- users study product image galleries on eCommerce pages to understand the specifics of a product they are interested in purchasing,

- users want to preview an experience they want to book (hotel, vacation, museum, theatre, restaurants) — in cases when they want to see large fullscreen images or videos while still being able to navigate between them back and forth,

- users explore content details as cards on mobile, swiping left and right.

In other words, carousels work when we provide additional content within a specific, and relevant context. All of these use cases are very typical for retail, tourism, product pages, galleries, related items, news stories and portfolios, among other things. That’s exactly where carousels shine.

Unfortunately, most of the time the ways we design carousels go very much against usability and accessibility, making carousels barely usable. Let’s explore a few techniques and strategies of how to change just that.

Indicate An Honest Scrolling DirectionCarousels come in various sizes and flavors. This goes for controls as much as for the direction of these controls. Sometimes we might encounter progress dots, and sometimes arrows, and sometimes we are expected to swipe (especially on mobile). Either way, the direction of the carousel’s control indicates expected movement when navigating the carousel. In a way, it’s a signpost that users read to understand the mechanics of the interaction. It goes without saying that it’s in our best interest to not break these expectations.

You and Oil (pictured above) features a carousel with a slider aligned vertically. How would you expect the carousel to work? How would you navigate through the slides? You might be inclined to drag the handle across the track, but it doesn’t do anything. You might then be inclined to click on the numbers, but it doesn’t do anything either. To navigate the carousel, you need to drag the slider from right to left. That’s unlikely to be expected by most users though. To solve this, we could flip the progress indicator by 90 degrees, turn it into a horizontal slider and place it above or below the content area.

The same problem appears on the Van Gogh’s museum website. The scrolling indicator is horizontal, yet one needs to scroll vertically to browse through available cards. Dragging the cards horizontally doesn’t seem to be supported. We could add prev/next buttons above the cards to help users navigate in a bit more predictable way.

If the carousel is moving horizontally, it’s only sensible to hint at expected behavior with a horizontal indicator. The same goes for vertical carousels in exactly the same way. It might sound a bit boring, but it will avoid quite a bit of confusion down the line.

Replace Progress Dots with LabelsWe are very much used to progress dots indicating the current position in carousels, but there are some good reasons why we might want to avoid them. For one, sometimes users desperately try to click on them, assuming that this is a supported interaction to navigate forwards and backward.

But because these dots are usually incredibly small, navigating via them — even if it’s supported — is slow and requires a lot of precision. Usually, this results in a feverish combination of rage clicks (or taps), mistakes, and unexpected jumps back and forth.

On the other hand, progress dots aren’t a particularly effective way to entice users to click through the carousel. They don’t communicate much; definitely not what each dot represents, nor what users should be expecting while sliding through the carousel. Progress indicators don’t convey any particular meaning (except the progress, that is), and thus aren’t very relevant to encouraging interaction.

On Platform Seven (picture above), it might not be very obvious what you are supposed to do to move forward and backward. Also, dots have different shapes and states which is difficult to decipher. Here, various sections of the page are grouped and highlighted with white background. This might not be very obvious to some readers. Here, progress dots do communicate the position in space, but they don’t necessarily invite users to explore that space, nor provide the reasons to do so.

The same problem also appears in regular navigation. Stripe Press doesn’t include a carousel but provides a navigation on the left. The design is outstanding, but hover is required to make sense of the sidebar navigation. Some sort of additional context, e.g. with labels or thumbnails, would probably help in discovery.

In general, it seems to be a good idea to never use progress dots as the only way for users to navigate the carousel.

One way to encourage navigation through the carousel is by adding more context to it. This could be done by using labels, thumbnails or video previews, for example. CreativeDenmark highlights each slide of the carousel with a distinct section, which is labeled and includes a video preview on hover. Unfortunately, the carousel isn’t keyboard-accessible. On mobile, the labels are rotated by 90 degrees — quite unusual, but because labels are relatively short, it might work in this scenario.

La Cité du Vin replaces progress dots with text labels to explain what a user should be expecting in the carousel. Unfortunately, most labels are impossible to read without clicking on them.

A circular full-height carousel on Squarespace Circle uses labels to highlight individual stories of contributors. Jumping to a story with some context of what the story is going to be about is a bit more compelling than clicking through lifeless progress dots.

Carousels don’t have to show only images — they can highlight video content as well. An example of a carousel with video slices is MySwitzerland.com. The carousel is auto-advancing, with video segments showing one after another. Each video segment is represented by a label, placed within a mini-navigation at the bottom left. Plus, the website is fully accessible with the keyboard — and it’s visually stunning, too!

Test what happens if you replace progress dots with meaningful labels or key highlights. Chances are high that carousels that used to have very poor click-through rates, suddenly will come to life. However, if your carousel has too many items, or labels are way too lengthy, there are alternative ways to encourage interaction.

Replace Progress Dots With A Horizontal SliderThe useful feature of progress dots is that they indicate progress. However, we don’t need to rely on them alone to show where a user currently is. One option is to use a horizontal slider to indicate how far the overall list of options actually is. That’s what Rolex does, accompanying the slider with an arrow to move forward step-by-step. This might be perfectly enough — and avoid rage clicks/taps on the individual dots.

On Tylko, a horizontal slider indicates the position in the carousel, with arrows pointing in both directions of movement. An interesting way to integrate user profiles, photos and customization options into one single component.

Bugaboo combines a progress slider with arrows located at the bottom of the carousel, along with hints that appear on hover. The carousel doesn’t auto-advance; the horizontal bar merely represents where the user currently is.

Adding a horizontal slider alone isn’t ideal though. Especially for longer carousels, it doesn’t convey enough information to indicate where exactly the user currently is in the carousel, and how far they have to go to make a full circle. We can invent various ways of showing progress — perhaps with percentages or a pie chart visualization, but probably the best one is the simplest one: numbers.

Daphne Wilde uses a non-conventional sliding numbers indicator to show where a user currently is. Users can also click on the images in the carousel to jump through available options. While this interaction isn’t necessarily obvious, numbers are large and easy to click and — most importantly — difficult to mis-tap.

The more complex our visualization of the progress is, the more issues it’s likely to bring up. Vallourec uses a pie chart indicator to highlight sub-sections individually while highlighting the section as well. Additionally, there is a bit of parallax-alike experience in place, combined with a vertical carousel.

Teatr Lalka, a puppet theater from Poland, with a creative, dynamic, and accessible approach to highlighting the position in the carousel (see the second image at the bottom). Each photo has a label, and it could potentially contain a short description, too. The entire website uses the metaphor of the puppet theater, with lovely transitions and animations. Beautifully designed, from start to finish.

26day.ge, a website dedicated to 100 years of Georgia's first Democratic Republic, uses numbers and transitions to swipe through the images in the little image gallery. The buttons are located under the carousel, they are grouped, and there is a little indicator of the position in the carousel, too. Admittedly, some transitions are a little bit too heavy though, especially on the frontpage.

No visual representation of progress can beat the clarity of numbers. If you do use a horizontal slider as an indicator of progress, consider adding numbers to highlight how many items there are in total, and where the user currently is. Deciphering ranges and filled bars are tricky. For shorter carousels this might not be as necessary, but it probably won’t hurt either.

Better Usability of Prev/Next ButtonsThis might sound a bit obvious, but it’s worth emphasizing: always include prev/next buttons to your carousels. Progress dots don’t necessarily indicate how exactly a carousel is supposed to be used. They do assume that users will be swiping left and right on mobile, yet not every implementation of the carousel supports that — and it might be not obvious at all on desktop.

Plus, sometimes swiping is quite unpredictable, with users underestimating their swiping speed and jumping too far, just to have to slowly swipe back to make sure they don’t skip anything relevant. On desktop, navigation through prev/next buttons is much more common and hence expected. Having a simple navigation pattern that that helps users navigate through the carousel in single steps can be a big help.

But then there are so many questions that appear about fine little details that go into prev/next buttons. For example, by how many items should a carousel “jump”? Should the user jump over all visible items that currently appear on their screen, or should the carousel slowly move one by one, requiring multiple taps to show new items? Or perhaps we should move by 2–3 items instead to make jumps more predictable?

When users feel that the movements of the carousel happen too quickly, they seem to have a hard time understanding how far they have jumped through. So they go back to verify that they didn’t miss anything relevant. While the movements step-by-step are slower, usually they cause fewer mistakes, and every now and again moving forward slowly is perfectly acceptable.

However, if users tend to browse through many items (10+ items) in a very lengthy carousel, jumping one by one is way too slow, and jumping by a couple of items is confusing since the beginning and the end of the list aren’t obvious with every jump. In that case, jumping by the entire visible list is probably going to bring better results. The final decision will ultimately lie with your studies on how your users actually navigate the carousel, and how far they browse in the list.

Keep Prev/Next Buttons CloseAnother question that comes up in conversations a lot is the best position of prev/next-buttons. We want to minimize errors, mistakes, and mishaps as far as possible, and usually, this means increasing tap sizes and adding enough distance between interactive elements. At the same time, we want to speed up navigation within the carousel as far as possible, and this means minimizing the distance between opposite actions: in our case, that’s moving forward and moving backward.

There is no shortage in available options. We could place the arrow above the carousel, center them vertically/horizontally on the carousel’s slices, or display them under the carousel. Additionally, we could group them and display them together, next to each other, or space them out, and show them on the opposite sides of the carousel.

Gram Museum displays prev/next buttons above the carousel — both on mobile and on desktop. They are a little bit small, and could probably be larger. The arrows are aligned to the edges of the carousel, rather than being grouped together.

On Stripe Life at Jobs, the arrows are placed on the carousel slices, centered vertically. In fact, that’s a very common decision, but depending on the audience you have, it can cause trouble. When arrows sit straight on the carousel slices, and because usually each slice is a link driving users to a landing page, users accidentally miss the hit target and end up clicking on the wrong page. This is critical when arrows don’t have enough padding.

Galaxus shows a very common pattern for eCommerce sites. Products are displayed within the carousel, with prev/next buttons on both edges of the carousel. Also note "Alle anzeigen" link in the right upper corner which displays all products on a separate page.

The design on Casper.com might appear exactly the same as in previous examples, but here the prev/next buttons are floating aside from clickable text and images, making it harder for users to mis-tap. However, once customers need to change the direction of the movement, they need to travel all the way back to the other side of the carousel’s galaxy, and then back. That distance travelled might be wasteful and unnecessary.

The distance that customers need to travel on Allianz.de is much shorter. Another common pattern is to display prev/next buttons next to the progress dots, under the carousel. The only potential issue is that some users might not understand that the visible sections are only a part of all available options and scroll down too quickly.

Notice the grouping of prev/next buttons in the last example. In fact, it seems to be a very good idea, as it aids users in navigation back and forth quickly without having to re-calibrate their mouse pointer or their fingers. Both options are close to each other, so going back and forth is faster than traveling all the way to another side of the carousel, and then back. Also, the option eliminates mishaps or misclicks.

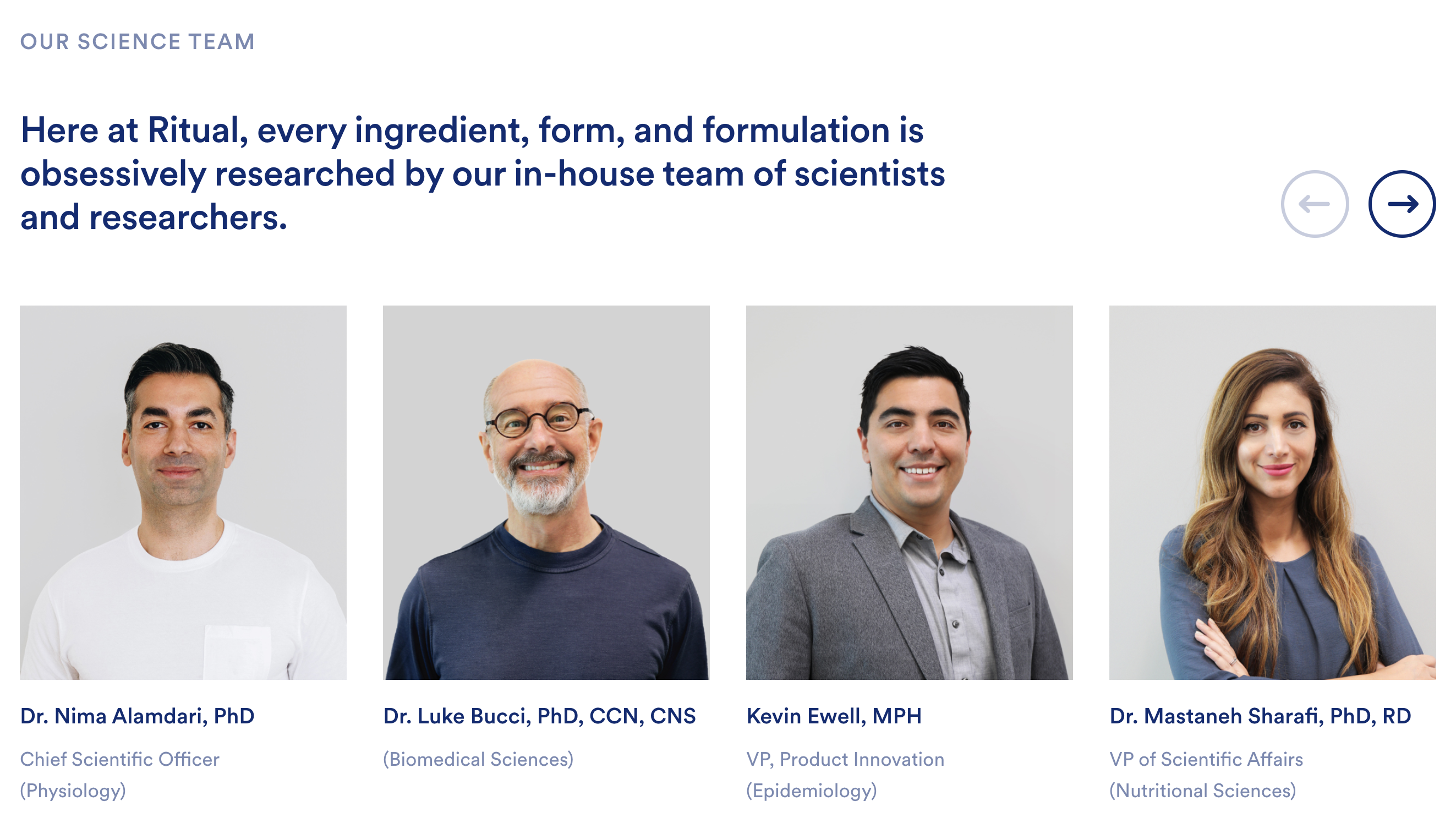

Arrows in use for testimonials on Ritual.com, beautifully integrated into the design, with videos and text snippets appearing as the user is sliding between the slices of the carousel. The arrows are grouped, but since no progress dots are used, they are positioned closer to the images. With this approach, it’s critical that hit target areas for arrows are large enough to prevent mistakes.

With 62 CSS pixels in width and height, it’s more than generous for precise input. Users can focus on a particular area, slightly detached from but connected to the the actual slides of the carousel, and click through precisely and predictably. A great example.

We don’t have to group the buttons horizontally though. On Overpass, the arrows live within the carousel, next to description and under the image. A vertical carousel could be an option, too.

Which one to choose? Test if grouping the buttons closely to each other will reduce mistakes when a carousel is used. The further away the buttons are from each other, the more time consuming and slow the carousel experience will appear to be. The remaining question is whether the buttons should live above the carousel, on it, or under the carousel. And this depends on the device the customer is using.

On Desktop, Buttons Live Above The CarouselThere is surely no universal solution, but in my experience, one ends up with fewer usability issues by placing buttons above the carousel. On the one hand, if the carousel lives all the way on the top of the page, we definitely want the prev/next buttons to be noticed early. If the buttons live under the carousel, they might not be noticed in time or not noticed at all, especially if carousel slices are very tall.

And if the buttons live right on the slides of the carousel, we end up with visibility issues of arrows as they might accidentally match the background color of the slide, and become invisible, or hard to decipher. Plus, users could accidentally jump to the wrong pages by clicking in just the wrong spot. We can solve all these issues with the buttons placed above the carousel.

A good reference example to keep in mind is Ritual.com mentioned above. The buttons are large. They are grouped. The distance needed to switch directions is minimal. The buttons also live above the carousel on desktop, leaving enough space for description to appear under individual images. Swipe gestures are also supported. The buttons and every carousel’s slide are keyboard-accessible. It’s just infinitely more difficult to make mistakes with this design.

On Mobile, Buttons Live Under The CarouselWhat do we do on mobile then? Well, on mobile, displaying prev/next buttons above the carousel is problematic. Depending on the height of the carousel’s slices and the position on the screen, every time a user interacts with the buttons via touch, they might be covering the content of the carousel with their fingers. Even the navigation heading in the same direction might make it necessary to lift a finger every time they want to consume content.

On the other hand, vertically center the buttons on the carousel is also problematic because taps are very inaccurate on mobile. Admittedly, as humans, we are much more precise in the center of the screen, but then we need large enough tap areas to avoid mistakes. And the larger tap areas are, the more space we will be taking away from our beloved carousels.

The only viable option left is to display prev/next-buttons under the carousel (on mobile). However, we need to be very cautious about the height of the carousel’s slices: they should never take up more 45–50% of the screen. This sounds like a magic number, but research shows that on mobile, we tend to interact with pages by reading and swiping and scrolling in the center of the screen.

If a user scrolls down to explore the carousel, we should expect them to spot the prev/next buttons because they will be in view. Plus, every time a user interacts with the carousel, their fingers will be far away from the carousel, so we shouldn’t be expecting accidental clicks/taps. Problems solved.

In summary, as long as the prev/next buttons are clearly detached from the content of the carousels and have a large tap area, they can be centered vertically and live on the edges of the carousel. For faster navigation forwards and backwards, we can place the buttons above the carousel on desktop, and under the carousel on mobile. This is just the least likely option to produce accidental mistakes.

Combine Tabs and CarouselsUsually, carousels are presenting content that users don’t have much control about. One way to make the carousel slightly more relevant is by adding filters to the carousels, allowing users to choose what exactly they’d love to see.

On Reuters.com, cards, tabs and a carousel complement each other, with the prev/next buttons to control the carousel placed in the upper right corner of the section. A great way to encourage users to click through topics of interest and explore available options — and also jump straight to the category with the “See all World” button. On mobile, the arrows jump under the carousel.

Federal Statistical Office in Switzerland relies on tabs to change the slice of the carousel. Initially the carousel auto-advances, but once a user has chosen one of the topics, it stays still. The height of all slices is the same, so there are no visual jumps, and no transitions from one side to another. A calm, respectful and functional solution.

On GetCruise.com, a tiny horizontal slider appears under the carousel, and the pointer changes to a custom indicator. The latter highlights that the area is draggable. In such a case, of course, the content area should be scrollable with a keyboard alone as well. On mobile, two arrows appear above the carousel, allowing users to jump between topics. No progress dots or sliders are in sight. This could work, too.

Use Thumbnails Or Icons To Encourage Click-ThroughsThe more relevant content we can display to encourage users to act on them, the higher click-through rates we should be expecting. Rather than using labels, Weber Grill Original uses thumbnails to highlight their recipes. This is probably going to work better than lifeless dots.

More of a tabbed navigation than a carousel: Philips.de. Icons requires less space, but can be mysterious if not chosen properly. Text labels could be a good compliment to the design, and either way they need to be communicated to screen reader users. Unfortunately, the carousel is auto-advancing, and there is no way to pause or stop it — even when hovering or focusing on the individual slices.

While some implementations rely on progress indicators, others rely on prev/next buttons and others rely on thumbnails, there are plenty of implementations that heavily rely on a single mode of interaction: dragging. Surely users do understand how to drag items on the screen, yet making dragging accessible is nothing short of impossible.

We definitely need to support swiping gestures on mobile, but this shouldn’t be the only method to navigate the carousel. On LeadDev, related articles are highlighted with a horizontal bar and a large green icon that indicate that a user can scroll left and right. Adding arrows to jump left and right might help users be more precise in their jumps.

On Magasins Generaux, the draggable icon is the only indicator that an image gallery is draggable. Admittedly, this isn’t a carousel, but unfortunately, the slides aren’t keyboard-accessible, and tabbing through the content brings users from the last link in the article to the footer. It should be possible to navigate to each image and announce its alternative text.

Add An Information Scent to The CarouselOne of the common issues in the carousel is the discoverability of slices that are coming in late in the carousel. One way of ensuring that users understand that they didn’t see everything just yet, is by adding some sort of information sent to the last visible slides or upcoming slides.

Neufuntrois.com is a beautiful restaurant website with different shapes used as carousel slices. Previous and next slides are cut off, making it very obvious to users that this content can be discovered.

Scroll back to the previous section and compare the first example to the second. You might find a significant difference. While the first example provides an information scent to the users, the second does not. Some browsers don’t display scrollbars, and on some screens, you might be hitting just the wrong resolution, so users won’t get any clues that some useful content is currently hidden and is just one swipe away.

On SRF, prev/next buttons are grouped and displayed on the right edge of the carousel, next to an upcoming slice which fades out. This makes it quite obvious that the user hasn’t seen all slides just yet, and can explore them if needed.

It’s a good idea to make sure that the last visible slide is either cropped or fades out, or use any other visual clue, also called information scent, that there is something out there to be discovered. If we don’t use any progress bar, nor indicate the overall number of slices, nor use any prev/next-buttons, we shouldn’t be expecting users understanding how the carousel works. If you want to avoid usability issues, sprinkle a bit of information scent on your carousel — your users might appreciate it.

Avoid Auto-Advancing, Or Add At Least 5–7s DelayAuto-advancing carousels temper with users’ patience and their priorities. Just like we’ve learned to ignore advertising banners, we tend to dismiss anything that’s blinking, moving or distracting us. This is true especially on mobile devices where users often scroll past the carousel too quickly to even notice that it’s actually auto-advancing. Any kind of unexpected movement rarely brings more attention to the carousel, but rather drives the attention away — both on mobile and on desktop.

However, if you absolutely need auto-advancing to draw and keep user’s interest, we could make it work as well — with a solid delay of 5–7s for each slide.

7h34, a lovely design agency website with a circular carousel, that flips clockwise. Users can also scroll up and down to jump through the slices of the carousel. The delay between auto-advancing is around 5s.

One way to improve it is to set the right expectations early on, so users get a sense about when the next slide of the carousel should be expected. Google Pixel Buds, for example, is auto-advancing and contains labels. The progress indicator is being filled gradually and slowly, with a 6s delay for each slide, providing enough time to act on the current slide, scroll down or leave the page altogether, without being interrupted along the way.

Timeless.ee uses trolley buses’ names that get filled in as the carousel is auto-advancing. The latter cycles through retro trolleybuses in Estonia available for booking or hiring. Like in the previous example, the filling speed indicates when the next slide should be expected. For some names, it takes slightly longer to fill in the name, but it’s always beyond 5s.

Ferrari.com highlights a current position in the carousel and uses a little circular indicator to explain that the carousel will auto-advance when the time expires. Ferrari also uses a 7s delay. Unfortunately, here it’s impossible to pause auto-rotation.

A slightly unusual auto-advancing experience on Casper.com, with the left bar growing, and accordions collapsing and expanding. The image doesn’t change as the text gets hidden and revealed. The delay for this experience is also 7s.

As Christian Holst has written previously:

“The amount of text in a slide should largely determine the duration of a slide’s visibility. If it’s just a short heading, 5 to 7 seconds proved to be appropriate in our tests, whereas longer durations were needed for more text-heavy slides. (Nielsen Norman Group recommends 1 second per 3 words for auto-rotating slides.) One consequence of this is that you might need to assign unique durations to individual slides, showing some slides longer than others.”Always Include A “Pause” Button For Auto-Advancing Carousels

If it’s absolutely critical to include an auto-advancing behavior for one reason or another, consider what goals the carousel is trying to achieve. Chances are high that a carousel won’t help you bring good leads or effective clicks. If it’s absolutely necessary, however, please make sure to include a “Pause” button as well, so users have an option to pause auto-rotation.

A great example of the implementation is Walmart.com (above). The carousel auto-advances slowly, but only if users don’t act on any of the images. Most importantly, there is a visible “Pause” button both on mobile and desktop and there is a focus/active state on the slider as well. Unfortunately, it’s a bit hard to say how many items are available in the carousel. Numbers would probably help here.

It goes without saying that auto-rotation should stop entirely when a user interacts with a slice of the carousel, be it by hovering, focusing, or tapping through available options. Interrupting the exploration of selected items is a safe way to drive users away from the carousel for good.

Alternatives to CarouselsWith all of these considerations in mind, one might assume that carousels are often the best solution. But that’s quite unlikely to be true. Personally, I’m yet to see a carousel that slashes all expectations by large and drives KPIs through the roof. In corporate environment where I often find myself, nobody really trusts me. I always have to argue about design decisions based on evidence coming from usability and accessibility tests, and rely on business metrics to drive these decisions.

Carousels rarely help in driving these metrics — mostly because they hide relevant content and hence make it less accessible. Cards, teasers, buttons, navigation all would probably work better for navigation. However, when it comes to highlighting features or products or offerings, rather than navigation options, they might work as well. If you have a strong feeling that a carousel isn’t really working, or is just the wrong component to use, run a test on a Saturday morning when there might be less traffic, and build up a case highlighting that another design might be driving higher KPIs.

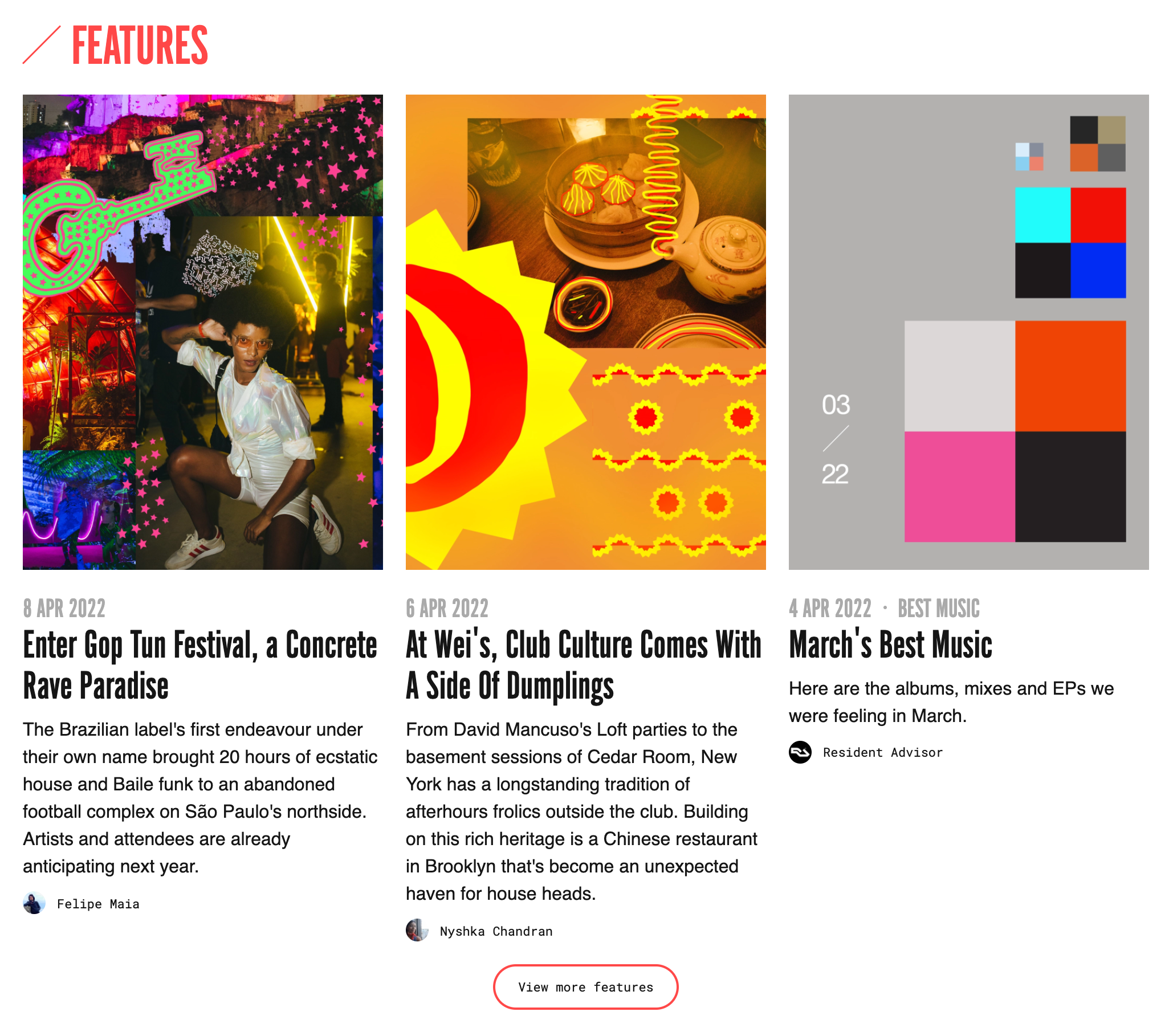

In fact, there is no shortage of alternatives to carousels, and often they are quite easy to implement. ResidentAdvisor avoid carousels altogether, highlight three last features, and invites users to explore more with a “View more features” button. The button could be loading more items or moving users to a separate page. A predictable and calm design that shows just enough text and visuals to entice a user to dive in.

Instead of using a carousel, Australia Post uses a dynamic layout to highlight all features together in the same area. There are some carousels in use on the page as well, but hiding features in the carousel would make them inaccessible to at least some users who’d just quickly scroll past it.

168plymouth uses mini-carousels for each feature that they want to highlight. There is no rotation, no auto-advancing, and you can move only in a single direction — moving backward might not be necessary with just 4 images that every panel contains.

Deutsches Museum uses the “load more” pattern to show more items if needed. This makes the front page quite compact, without too many items appearing all over the page at a given time.

All of it is to say that not every page needs a carousel, and very often it might be a wrong and unnecessary pattern to use — so be cautious when using it, and explore alternatives as a part of your design process.

Wrapping UpCarousels have many accessibility and usability issues, from discoverability to accessibility. In a way, very much like accordions, they provide a way to show and hide some pieces of content — either manually or automatically. And that’s not something that many other components have.

When designing your next carousel, think about whether it could be replaced with another design pattern that would be serving content discoverability slightly better. If it’s out of the question, consider replacing progress indicators with labels or thumbnails. Indicate the current slice of the carousel. Include and group prev/next buttons and display them above or below the carousel. Use numbers to explain where users are and how far they can go. Resist auto-advancing as much as you can, and if you can’t, add a delay of 7s and allow users to pause rotation.

Carousel UX ChecklistAs usual, here’s a general checklist of a few important guidelines to consider when designing better carousels:

- Choose the sequence of slides carefully.

- Most important slides always come first.

- Limit the height of the slides to 45-50% of the screen’s height (max).

- Slides shouldn’t rotate too quickly (min delay of 5–7s).

- Try to avoid auto-rotation on mobile.

- Always pause auto-rotation on hover, stop on interaction.

- Don’t rely on dragging the carousel alone.

- Make sure the slides are keyboard-accessible.

- Always support swipe gestures on mobile.

- Always indicate a slice of the upcoming slide.

- Always show at which slide a user currently is.

- Consider replacing progress dots with labels, thumbnails, key highlights.

- On desktop, group prev/next steps and display them above the carousel.

- On mobile, group prev/next steps and display them below the carousel.

- Combine carousels with navigation, tabs, or filters.

If you are interested in similar insights around UX, take a look at Smart Interface Design Patterns, our shiny new 6h-video course with 100s of practical examples from real-life projects. Plenty of design patterns and guidelines on everything from accordions and dropdowns to complex tables and intricate web forms — with 5 new segments added every year. Just sayin’! Check a free preview.

Meet Smart Interface Design Patterns, our new video course on interface design & UX.

Meet Smart Interface Design Patterns, our new video course on interface design & UX.

100 design patterns & real-life

examples.

6h-video course + live UX training. Free preview.

- “Designing Effective Carousels,” Kara Pernice, Nielsen Norman Group

- “Auto-Forwarding Carousels and Accordions Annoy Users and Reduce Visibility,” Jakob Nielsen, Nielsen Norman Group

- “Creating Effective Carousels,” Steven Hoober, UX Matters

- “10 UX Requirements for a User-Friendly Homepage Carousel Design,” Christian Holst and Jamie Appleseed, Baymard Institute

If you find this article useful, here’s an overview of similar articles we’ve published over the years — and a few more are coming your way.

Related Articles

- Designing A Perfect Infinite Scroll

- Designing Perfect Breadcrumbs

- Designing A Perfect Accordion

- Designing A Perfect Responsive Configurator

- Designing A Perfect Birthday Picker

- Designing A Perfect Date and Time Picker

- Designing A Perfect Feature Comparison

- Designing A Perfect Slider

- “Form Design Patterns Book,” written by Adam Silver