Frustrating Design Patterns: Broken Filters

Filters are everywhere. While we often think of them appearing when booking flights or shopping online, filters are frequently used in pretty much every interface that features more than a handful of data points.

It’s not necessarily just the sheer amount of data that is difficult to make sense of though; it’s the complexity and lack of consistency that the data usually entails which requires some filtering — such a common scenario in data grids, enterprise dashboards, vaccine tracking and public records registries.

Part Of: Design Patterns

- Part 1: Perfect Accordion

- Part 2: Perfect Responsive Configurator

- Part 3: Perfect Date and Time Picker

- Part 4: Perfect Feature Comparison

- Part 5: Perfect Slider

- Part 6: Perfect Birthday Picker

- Part 7: Perfect Mega-Dropdown Menus

- Part 8: Perfect Filters

- Subscribe to our email newsletter to not miss the next ones.

As customers, we use filters to reduce a large set of options to a more manageable and highly relevant selection. Perhaps just a few dozens of payment slips instead of thousands, or just a handful of blouses rather than the entire collection.

We have specific attributes of interest, a specific intent, that we need to somehow communicate to the interface. We do so by breaking our intent down into a set of available features. That intent might be fairly specific or quite general, but in both cases, the design should minimize the time needed for customers to get from the default state (when no filters are selected) to the final state (when all filters are successfully applied).

That’s only one part of the story though. Applying relevant filters is the easy part, but showing just enough relevant results is slightly more difficult. In fact, for every interface, and for every intent, we have a particular comfortable range in mind, that is a preferred number of options that we think we can manage relatively effortlessly.

This range of options doesn’t have to fit on a single screen, or be displayed on a single page, or be limited to a small shortlist that we can easily remember. It can be anything from dozens to hundreds of items scattered over a number of pages.

The important part is that this range meets our expectations that:

- we are looking at highly relevant options,

- we can easily understand what we are exploring,

- we can spot the differences between all options, and

- we can process everything within a reasonable, foreseeable timeframe.

Unlike sorting, which merely rearranges the results according to some preferred attributes (soft boundaries), filters always represent hard boundaries. They strictly limit the scope of results. Not enough proper filters and users shoot way over the comfortable range; too many filters and users end up with zero-results and abandon the site altogether.

The comfortable range varies significantly from a product to product. The cue to where it lies can be inferred from how different the options actually are. In usability tests, we see people having no issues exploring 20–30 kinds of vehicles, 40–50 kinds of sneakers, 70–80 bouquets of flowers, or even paginating through 100–200 payment slips. Yet they feel utterly overwhelmed when exploring 15 different types of sharpies or AAA-batteries. As a rule of thumb, it seems that the more different the options are, the more comfortable we feel with a slightly larger set of options.

The ultimate question, then, is how to find that delicate balance, when our interface helps users quickly arrive at just enough results. One answer to that question lies in something that sounds awfully obvious: eliminate any roadblocks on users' path towards that comfortable range. It’s easier written than done though — especially when you have dozens or even hundreds of filters that have to be accessible on mobile, on desktop, and everywhere in-between.

The Complexity of FilteringAt the first glance, filtering doesn’t seem like a particularly complex endeavour. Of course we can have lengthy debates about the right form elements for different kind of filters — autocomplete, radios, toggles, select-dropdowns, sliders and buttons just to name a few — but in their essence, all of the form elements are just basic input, right?

Well, as it turns out, there are quite a few facets of the experience that make designing filters quite difficult:

- filters can come in various flavours and shapes, for pricing, ratings, colors, dates, times, size, brand, capacity, features, level of experience, age range, symptoms, product status etc.

- filters usually come in large numbers, and they need to be displayed across screens,

- filters often have different states (selected, unselected, disabled)

- filters often need sensible defaults, and they have to remember user’s input,

- filters can be interdependent, and these dependencies need to be obvious,

- filters can be difficult to validate, e.g. when users can type in complex data, such as time or dates,

- filters need to support and show meaningful error messages,

- and so many others.

Filters never exist on their own; in one way or another, they are always connected to the results that they are acting upon. This connection often causes filters and matching results to be somewhat synchronous, as the latter depend on how fast the UI registers an input, and how much time it needs to successfully process it.

Now, addressing all the fine intricacies of each of these challenges is nothing short of monumental work, yet some issues are slightly more frustrating than others, making the overall experience painful and annoying, and hence causing high abandonment and high bounce rates. Let’s explore some of the critical ones.

Avoid Tiny Scrollable PanesAfter just a few usability sessions with customers who try to use filters on their own device, one can spot some common frustrations making rounds over and over again. One of the most annoying patterns comes from lengthy filter sections that contain dozens of options. These options often get tucked away in a tiny scrollable pane, showing 3–4 options at a time and requiring vertical scrolling to browse the options.

These sections often cause customers to scroll vertically, slowly, accurately, with extreme focus and precision. As they do on mobile, some filters get activated by mistake, prompting the customer to be even more focused. A classic example of this pattern is the “Brands” filter, which often contain hundreds of options, sorted by popularity or by alphabet.

An alternative option would be to show as many as 7–10 options at a time with an accordion that would expand and show all options on tap/click. These options don’t have to be displayed in their full height, but can live in a larger scrollable pane, but then they shouldn’t be activated by scrolling through the pane.

It’s also a good idea to compliment the filter with a search autocomplete and an alphabetical view if some of the popular options are highlighted at the top. A good example of it is Rozetka.ua, an eCommerce retailer from Ukraine (see above).

Always Provide Text Input Fallback For SlidersWhenever users can define a large range of values, be it pricing range in retail store, max duration of a train trip or a min/max coverage for an insurance plan, we probably will use some sort of a slider. All sliders have one thing in common: they are wonderful when we want to encourage customers to explore many options quickly, but they are quite frustrating when the user has something specific in mind and hence needs to be a little bit more precise.

Just think about the frustration we usually have to go through when bumping up the price a little bit, from $200 to $215, or adding another hour for the duration of your flight. Doing so with a slider is difficult because it requires incredible precision, and that always causes mistakes and frustrations.

We’ve covered how to design a perfect slider in detail already, but probably the most important feature that every slider needs is to support different speeds of interaction. In fact, there are a few common types of interaction:

- when customers want to explore many options quickly, a good ol’ slider with a track and a thumb works perfectly fine;

- when customers to be more precise in their exploration, we can help by adding steppers (+/-) for granular jumps forward and backwards,

- when customers have an exact value in mind, we can help by providing text input fields for min/max values, so users can type in values directly without having to use the slider,

- in all of these cases, solutions have to be accessible and support keyboard-only interaction.

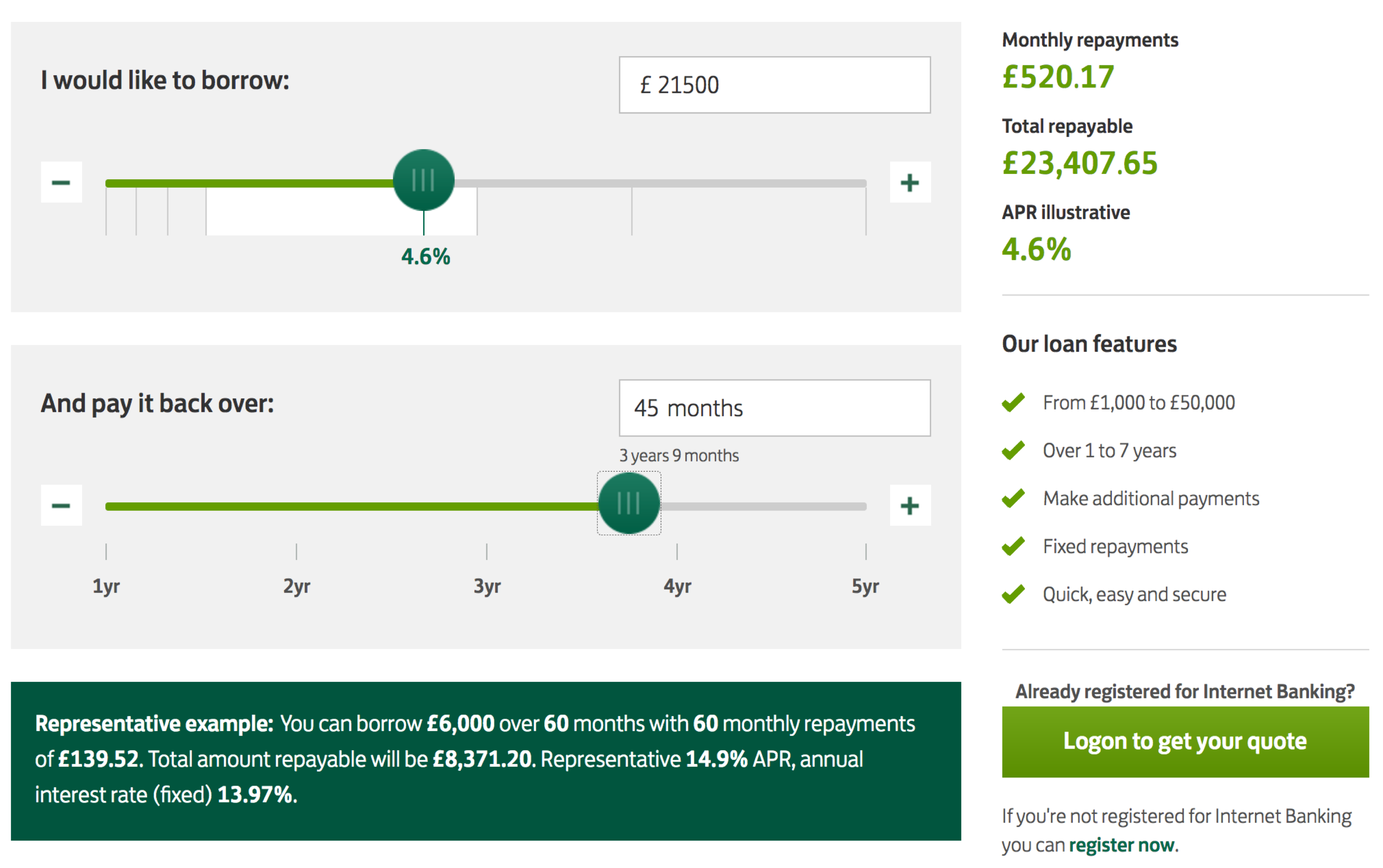

Take a look at the Lloydsbank’s example below. A personal loan calculator supports all types of interaction beautifully. Also, notice the focus styles when the thumb is activated, and ranges displayed below the interest rate slider at the top to indicate where the customer is currently navigating. The interest rate changes depending on how much money the customer would like to borrow.

Another intersting example of a well-designed slider comes from Made.com’s Sofasizer, which allows you to filter couches based on the dimensions that they need to have. Rather than using a set of input fields, Made.com chose to use a visual interface with a “Resize” icon. You can drag the handle to adjust the size, or you can type in exact values in the height and width input fields.

Another option is to turn all filter sections into overlays and display them on tap/click above the results. In fact, you could even use floating filters, so as the customer scroll down the page, the filters are always still accessible.

An example of this pattern is Adidas (see the image below). The filters bar is persistent; even as users are scrolling down the page, the filter overlay won’t close automatically — it requires user’s input, again handing over the control to the user. However, it does close automatically once one of the filters is selected. If the user wants to select multiple filters, they have to re-open the same filter group over and over again. Keeping the filters persistent might be a better idea. Still, the result: no layout shifts, no frustrating scrolling in narrow corridors, and filters always accessible.

Not to say that displaying filters above the results is always better by default. On Asos, every filter input causes jumps to the top of the page, so customers have to manually scroll down to continue filtering. Instead of re-rendering the entire page, it would make more sense to re-render only the filters area and the product list.

Ikea features filters at the top of the results. Sometimes filters appear in a drop-down overlay, and sometimes as a pill below the filters. But most of the time, unlike previous examples, when a filter is selected, it displays a sidebar mega-filter-overlay on the right with all available filtering options grouped there. As the customer is making their way through the filters, the product list is updated in the background asynchronously. More importantly, notice the “Apply” button which label changes depending on the input.

With every filter input, a new request is sent to the server, retrieving the number of results, and then showing them in the UI. That’s a great way to give users a very clear sense of how far or how close they are towards their comfortable range.

Another example is Galaxus.ch (see below), a Swiss eCommerce retailer that provides a first-class experience when it comes to filtering. The filters are displayed above product results; a filter overlay appears on tap/click. No slowdowns, fast response times and a lovely integration of active filters with the filters area. A great reference example that is worth considering when designing any kind of filter.

In general, having an “Apply” button along with real-time updates of the content area seems to be working best. It really combines the best of both solutions: showing results immediately when they arrive, while keeping filters accessible at all times.

Avoid Split-Screens On MobileThe issues that we’ve explored in the article apply equally for large and for small screens. However, on small screens, and especially on slow connections, these issues become even more critical. Most of the time, interfaces tend to block the entire UI on a single filter input, causing massive delays for customers on the go (e.g. Crutchfield, Walgreens). On the other hand, it’s common to split the screen to display a filters overlay, while still showing the product list updated in the background (e.g. Nordstrom).

In general, though, it might be a better idea to experiment if a full-page overlay for filters would perform better. It gives more space to experiment with a multi-column view, or perhaps even display a swipeable area to choose filters without having to move between separate pages. In fact, using accordions that could collapse and expand instead of bringing the user to a separate page might be a good idea — similar to what we’ve discussed with mega-dropdowns.

Unlike on desktop, having an “Apply” button in all these examples matters, and you can make it slightly more useful by adding the amount of products as a label on the button and keeping the button sticky at the bottom as the user is scrolling down.

Filtering Design ChecklistAs usual, here are all the things to keep in mind when designing any kind of filter — a little helper to not forget something important before heading into conversations with your fellows designers and developers. You can find a full deck of Smart Interface Design Patterns Checklists at yours truly Smashing Magazine as well.

- Can we avoid a filter icon and show filters as they are?

- If not, what icon do we choose to indicate filtering?

- Is the icon + padding large enough for comfortable tapping?

- Do we put the icon at the top, bottom or floating (mobile/desktop)?

- What exactly happens when the user clicks/taps on the icon?

- How will the icon change on tap/click?

- Will we have some sort of animation or transition on click?

- Will filters appear as full page/partial overlay or slide-in?

- Can we avoid sidebar filtering as it’s usually slow?

- Do we expose popular or relevant filters by default?

- Do we display the number of expected results for each filter?

- Can we use a horizontal swiper to move between filters?

- Can we avoid drop-downs and use only buttons/chips + toggles?

- For complex filters, do we provide search within filters?

- Do we use icons to explain differences between various filters?

- Do we use the right elements for filters, e.g. sliders, buttons, toggles?

- Do filters apply automatically (yes, for slide-ins)?

- Do filters apply manually on confirmation (“Apply”) (yes, for overlays)?

- How do we communicate already selected filters?

- Can selected filters appear as removable pills, chips or tags?

- Do we recommend relevant filters based on selection?

- Do we track incompatibility between selected filters?

- How do error messages or warning appear in the UI?

- Do we allow customers to reset all filters quickly, at once?

- Are filters (or filters button) floating on scroll on mobile/desktop?

- Can users tap on the same spot to open/close filters?

Too often the filtering experience on the web is broken and frustrating, making it just unnecessarily difficult for customers to get to that shiny comfortable range of relevant results. When designing the next filter, take a look at some of the common issues that you might want to avoid, and hopefully avoid all the frustration that comes from broken, frozen and inaccessible filters.

- Design for the comfortable range of options and for the case when a customer wants to add multiple filters quickly — one right after another.

- For lengthy filter groups, avoid tiny scrollable panes and show as many as 7–10 options at a time with an accordion that would expand and show all options on tap/click. Add a search autocomplete and an alphabetical view as well.

- Always add steppers (+/-) and text input fields when using sliders,

- Customer often want to set a number of filters of the same type. Never auto-scroll users on a single input and never collapse a group of filters automatically.

- Never freeze the UI on a single input, and never make your customer wait for an interface to respond back when setting filters.

- Always update filters and show results asynchronously, so that on every filter input, matching results could be updated asynchronously, while the filters always remain accessible and at the same place.

- Always avoid layout shifts on filter input and consider displaying filters above the results.

- On mobile, “Apply”-button could be sticky at the bottom of the screen. Update the count of products and show them on the button.

Related Articles

If you find this article useful, here’s an overview of similar articles we’ve published over the years — and a few more are coming your way.

- Perfect Accordion

- Perfect Responsive Configurator

- Perfect Birthday Picker

- Perfect Date and Time Picker

- Perfect Mega-Dropdown

- Perfect Feature Comparison

- Perfect Slider

- Form Design Patterns Book by Adam Silver, published on SmashingMag

- Subscribe to our email newsletter to not miss the next ones.